Linear Maps Between Vector Spaces: Examples and Problems

Examples and Problems

Example 1

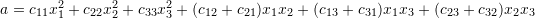

Consider the symmetric matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}1&1&0\\1&1&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-24f78f677770a87684f246f9c60f8004_l3.png)

Find ![]() , the determinant of

, the determinant of ![]() , the kernel of

, the kernel of ![]() , the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of ![]() , and find the coordinate transformation in which

, and find the coordinate transformation in which ![]() is diagonal.

is diagonal.

Solution

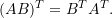

Since ![]() is symmetric, therefore,

is symmetric, therefore, ![]() . The determinant of

. The determinant of ![]() can be obtained using the triple product of the row vectors. However, it is obvious that the first two vectors are linearly dependent (they are equal), therefore,

can be obtained using the triple product of the row vectors. However, it is obvious that the first two vectors are linearly dependent (they are equal), therefore, ![]() . The kernel of

. The kernel of ![]() can be obtained by finding the possible forms for the vector

can be obtained by finding the possible forms for the vector ![]() that would satisfy the following equation:

that would satisfy the following equation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Mx=0\Rightarrow\left(\begin{matrix}1&1&0\\1&1&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}x_1\\x_2\\x_3\end{array}\right)=0 \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9b272913dfbb8745fb0b39fab4c36f17_l3.png)

Therefore:

![]()

By setting ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() . Therefore, the kernel of

. Therefore, the kernel of ![]() has the form:

has the form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \ker{M}=\left\{x=\left(\begin{array}{c}\alpha\\-\alpha\\0\end{array}\right)\bigg| \alpha\in\mathbb{R}\right\} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d9a0b733d826d1ca42f54a243d2ff01b_l3.png)

To find the eigenvalues of ![]() we find the possible values for

we find the possible values for ![]() that would make the matrix

that would make the matrix ![]() not invertible. In other words, we solve for

not invertible. In other words, we solve for ![]() that would satisfy:

that would satisfy:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \det{M-\lambda I}=0\Rightarrow \det\left(\begin{matrix}1-\lambda&1&0\\1&1-\lambda&0\\0&0&1-\lambda\end{matrix}\right)=0 \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b27ad946c5fea7062e1e3e8b318e7416_l3.png)

Therefore:

![]()

Therefore, the possible three eigenvalues are: ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Note that since

. Note that since ![]() is not invertible,

is not invertible, ![]() is automatically an eigenvalue for

is automatically an eigenvalue for ![]() .

.

The eigenvector ![]() corresponding to the eigenvalue

corresponding to the eigenvalue ![]() can be found as follows:

can be found as follows:

![]()

which is the same equation to find the vectors of the kernel. So, a normalized vector in the kernel would satisfy this equation. Therefore,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ ev_1=\left(\begin{array}{c}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\\\frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}}\\0\end{array}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-35da8891223eaf79904898d72864aa31_l3.png)

The eigenvector ![]() corresponding to the eigenvalue

corresponding to the eigenvalue ![]() can be found as follows:

can be found as follows:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M(ev_2)=1 (ev_2) \Rightarrow \left(\begin{matrix}1&1&0\\1&1&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}{ev_2}_1\\{ev_2}_2\\{ev_2}_3\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c}{ev_2}_1\\{ev_2}_2\\{ev_2}_3\end{array}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3083e3a97b1b2c95b86e32db8b9f4067_l3.png)

Therefore, we have the following three equations:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Therefore, the normalized components of the second eigenvector are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ ev_2=\left(\begin{array}{c}0\\0\\1\end{array}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-001feb7e8480073a8810dee829ae8001_l3.png)

Since ![]() is symmetric, the third eigenvector has to be normal to the first and second eigenvectors. So, we can simply find a vector normal to

is symmetric, the third eigenvector has to be normal to the first and second eigenvectors. So, we can simply find a vector normal to ![]() and

and ![]() . Or we can solve the equation:

. Or we can solve the equation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M(ev_3)=2 (ev_3) \Rightarrow \left(\begin{matrix}1&1&0\\1&1&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}{ev_3}_1\\{ev_3}_2\\{ev_3}_3\end{array}\right)=2\left(\begin{array}{c}{ev_3}_1\\{ev_3}_2\\{ev_3}_3\end{array}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ae1dd84d078475ddfc13a116816261c6_l3.png)

Therefore, we have the following three equations:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Therefore, the normalized components of the third eigenvector are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ ev_3=\left(\begin{array}{c}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\\\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\\0\end{array}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-729d180bfc2c9127e26ba693929602f4_l3.png)

The coordinate system in which the representation of the matrix ![]() is diagonal is the coordinate system made of the three normalized eigenvectors of

is diagonal is the coordinate system made of the three normalized eigenvectors of ![]() . Setting

. Setting ![]() , the coordinate transformation matrix

, the coordinate transformation matrix ![]() has the form:

has the form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Q=\left(\begin{matrix}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&0\\\frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4970125ea4a6ec808aad2a43fb842e8d_l3.png)

Note that the order of the vectors in ![]() was chosen so that

was chosen so that ![]() is a rotation matrix, i.e., the vectors of

is a rotation matrix, i.e., the vectors of ![]() have to obey the right hand orientation. Therefore, the components of

have to obey the right hand orientation. Therefore, the components of ![]() when using

when using ![]() as the basis set are:

as the basis set are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M'=QMQ^T=\left(\begin{matrix}2&0&0\\0&0&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-50b0e047a2264ec7f742e63af22063a8_l3.png)

Study the following Mathematica code and note the various functions used for matrix manipulations. Note that the function “NullSpace” can be used to find the vectors in the kernel. The actual kernel is the span of these vectors. Matrix multiplication is performed using the “.” character. Note also that the command “Eigensystem” in Mathematica can be used to produce the list of eigenvalues, followed by the list of eigenvectors. Study the code to see how the eigenvectors can be extracted, normalized, and then used to form the matrix ![]() .

.

View Mathematica Code

M = {{1, 1, 0}, {1, 1, 0}, {0, 0, 1}}; Mt = Transpose[M] Det[M] NullSpace[M] a = Eigensystem[M] ev1 = a[[2, 1]]/Norm[a[[2, 1]]] ev2 = a[[2, 3]]/Norm[a[[2, 3]]] ev3 = a[[2, 2]]/Norm[a[[2, 2]]] Q = {ev1, ev2, ev3}; Q // MatrixForm Mp = Q.M.Transpose[Q]; Mp // MatrixFormView Python Numpy Code

import numpy as np from numpy.linalg import * from scipy.linalg import * M = np.array([[1, 1, 0], [1, 1, 0], [0, 0, 1]]) print("M^T=\n",M.transpose()) # transpose matrix print("Det (M) =",det(M)) # determinant print("Vectors in the Kernel (Nullspace)=\n",null_space(M)) # null space unit matrix eigen = eig(M) # eigen values and vectors print("eigenvectors and eigenvalues\n",eigen) # first index is eigen values print("Eigenvalues = \n",eigen[0]) # Columns are normalized eigenvectors. Transpose is used to convert them into rows print("Eigenvectors = \n",eigen[1].T) #The rotation matrix is made out of the rows of the eigenvectors Q=eigen[1].T print("Q =\n",Q) # @ is matrix multiply print("Q.M.Q^T=\n",Q@M@Q.transpose()) # this also works print("Q.M.Q^T=\n",Q.dot(M).dot(Q.transpose()))View Sympy Python Code

from sympy.matrices import Matrix import sympy as sp sp.init_printing(use_latex = "mathjax") M = Matrix([[1, 1, 0], [1, 1, 0], [0, 0, 1]]) # transpose matrix display("Transpose =",M.T) # determinant display("Det=",M.det()) # null space display("Vectors in the Kernel (Nullspace) =",M.nullspace()) # eigen values display("Eigenvalues=",M.eigenvals()) # eigen vectors vector = M.eigenvects() display("Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors =",vector) ev = [i[2][0].T for i in vector] display("extracted eigenvectors",ev) #The function Matrix ensures the list is a sympy matrix Q = Matrix([i/i.norm() for i in ev]) display("normalized eigenvectors",Q) display("Check that triple product is positive") Q[0,:].dot(Q[1,:].cross(Q[2,:])) # matrix multiply display("Diagonalized matrix = Q.M.Q^T",Q*M*Q.T) Q2 = Matrix([Q[2,:],Q[0,:],Q[1,:]]) display("A different order could be used for Q",Q2) display("Diagonalized matrix = Q.M.Q^T",Q2*M*Q2.T)

Example 2

Consider the vectors ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Consider the linear map represented by the matrix:

. Consider the linear map represented by the matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}2&1&0\\1&5&2\\2&-1&3\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f479150533a4fe10b49b652344b9903a_l3.png)

- Find the components of the vector

, the image of the vector

, the image of the vector  under the linear map

under the linear map  .

. - Show that the vectors

, and

, and  form an orthonormal basis set.

form an orthonormal basis set. - Find the components of

and

and  if the basis set

if the basis set  is chosen for the coordinate system.

is chosen for the coordinate system.

Solution

The components of ![]() are:

are:

![]()

The vectors ![]() , and

, and ![]() are orthogonal to each other and the norm of each is equal to 1. In addition, the order

are orthogonal to each other and the norm of each is equal to 1. In addition, the order ![]() , and

, and ![]() follows the right hand orientation. Setting

follows the right hand orientation. Setting ![]() the coordinate transformation matrix is:

the coordinate transformation matrix is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Q=\left(\begin{matrix}u\cdot e_1&u\cdot e_2&u\cdot e_3\\v\cdot e_1&v\cdot e_2&v\cdot e_3\\w\cdot e_1&w\cdot e_2&w\cdot e_3\end{matrix}\right)=\left(\begin{matrix}0.6&0.8&0\\-0.8&0.6&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-61d04d40403cc1802a9222e27e1a93eb_l3.png)

Therefore, the components of the vectors ![]() , and the matrix

, and the matrix ![]() are:

are:

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M'=QMQ^T=\left(\begin{matrix}4.88&1.16&1.6\\1.16&2.12&1.2\\0.4&-2.2&3\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-840fa8c60495b1727ab36f44719c7b76_l3.png)

View Mathematica Code

x = {1, 1, 1};

M = {{2, 1, 0}, {1, 5, 2}, {2, -1, 3}};

Print["y=Mx"]

y = M.x;

y // MatrixForm

u = {3/5, 4/5, 0};

v = {-4/5, 3/5, 0};

w = {0, 0, 1.};

Norm[u]

Norm[v]

Norm[w]

u.v

u.w

v.w

Q = {u, v, w};

Q // MatrixForm

xp = Q.x;

Print["x'"]

xp // MatrixForm

yp = Q.y;

Print["y'"]

yp // MatrixForm

Mp = Q.M.Transpose[Q];

Print["M'"]

Mp // MatrixForm

Print["M'x'"]

Mp.xp // MatrixForm

View Numpy Python Code

import numpy as np

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import *

x = np.array([1, 1, 1])

M = np.array([[2, 1, 0], [1, 5, 2], [2, -1, 3]])

# matrix multiply

y = np.matmul(M,x)

# same operation

y = M@x

print(y)

u = np.array([3/5, 4/5, 0])

v = np.array([-4/5, 3/5, 0])

w = np.array([0, 0, 1])

print("Check length of vectors")

print("|u|=",norm(u))

print("|v|=",norm(v))

print("|w|=",norm(w))

# @ also works as dot product

print("Check orthogonality")

print("u.v =",u@v)

print("u.w =",u@w)

print("v.w =",v@w)

print("Check orientation")

print("u.v\u00D7w=",u@np.cross(v,w))

# Q will be a 3 x 3

Q = u

# Adds row to matrix

Q = np.vstack([Q, v])

Q = np.vstack([Q, w])

print("Q=\n",Q)

#Alternatively, Q can be defined as:

Q=np.array([u,v,w])

print("Q=\n",Q)

print("x=\n",x)

xp = Q@x

yp = Q@y

Mp = Q@M@Q.transpose()

print("x'=\n",xp)

print("y=\n",y)

print("M=\n",M)

print("M'=\n",Mp)

print("y'=M'x'=\n",Mp@xp)

print("y'= Qy\n",yp)

View Sympy Python Code

from sympy.matrices import Matrix

import sympy as sp

sp.init_printing(use_latex = "mathjax")

# vector []

x = Matrix([1, 1, 1])

M = Matrix([[2, 1, 0], [1, 5, 2], [2, -1, 3]])

y = M*x

display(y)

# you need [[]] to use matrix operations

ul = [3/5, 4/5, 0]

vl = [-4/5, 3/5, 0]

wl = [0, 0, 1]

u = Matrix(ul)

v = Matrix(vl)

w = Matrix(wl)

display("Check the length of each vector")

display(u.norm())

display(v.norm())

display(w.norm())

display("Check the mutual orthogonality")

display(u.dot(v))

display(u.dot(w))

display(v.dot(w))

display("Check the orientation")

display(u.dot(v.cross(w)))

Q = Matrix([ul,vl,wl])

xp = Q*x

Mp = Q*M*Q.T

yp1 = Q*y

yp2 = Mp*xp

display("Change of coordinate system matrix=",Q)

display("x in new coordinate system=x'=Qx",xp)

display("M in new coordinate system=M'=QMQ^T",Mp)

display("y in new coordinate system=y'=Qy",yp1)

display("y in new coordinate system=y'=M'x'",yp2)

Example 3

In the following code, the rotation matrix ![]() is defined using the function “RotationMatrix[angle]”. Notice that the angle input is automatically set at radians unless the command “Degree” is used. Because of the symbolic notation of Mathematica, the function FullSimplify[] is used to show that the rotation matrix preserves the norm of the vector

is defined using the function “RotationMatrix[angle]”. Notice that the angle input is automatically set at radians unless the command “Degree” is used. Because of the symbolic notation of Mathematica, the function FullSimplify[] is used to show that the rotation matrix preserves the norm of the vector ![]() after rotation and that the rotation angle between

after rotation and that the rotation angle between ![]() and its image

and its image ![]() is exactly 20 degrees.

is exactly 20 degrees.

View Mathematica Code

Q=RotationMatrix[Pi/6];

(*The following is a rotation matrix using 20 degrees*)

Q=RotationMatrix[20Degree];

u={2,2};

v=Q.u;

Norm[u]

Norm[v]

FullSimplify[Norm[v]]

VectorAngle[u,v]

FullSimplify[VectorAngle[u,v]]

View Numpy Python Code

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import *

# input degrees get radians

theta = np.radians(20)

c, s = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

# using the 2D rotation formula

Q = np.array([[c, -s], [s, c]])

print("Q =\n",Q)

u = np.array([2, 2])

v = Q@u

print("v =",v)

print("|u| =",norm(u))

print("|v| =",norm(v))

# using angle formula

th=np.arccos(u@v/norm(u)/norm(v))

print("theta(rad) =",th)

View Sympy Python Code

Example 4

In the following code, an array of 4 points is defined and used to draw a triangle. Then, a new array is calculated by applying a rotation of 60 degrees to every point and thus a new triangle rotated by 60 degrees is defined. Finally, two triangles are created using the Polygon function and viewed using the Graphics function.

View Mathematica Code

Q=RotationMatrix[th];

(*The following line stores the array of 4 vertices in the variable Points*)

Points={{0,1},{5,1},{2,3},{0,1}};

(*The following line rotates each of the 4 elements in Points using the rotation matrix Q, then, forms a new array of 4 rotated vertices in the variable Points2. The new array is formed using the Table command*)

Points2=Table[Q.Points[[i]],{i,1,4}];

(*The following lines define two polygons c and c2 using the vertices defined in the variable Points and Points2*)

c=Polygon[Points];

c2=Polygon[Points2];

(* The following line views the objects c and c2 with the default graphics formatting*)

Graphics[{c,c2},Axes->True,AxesOrigin->{0,0}]

(*The following line views the objects while applying specific graphics formatting*)

Graphics[{Opacity[0.6],c,c2},Axes->True,AxesOrigin->{0,0},AxesStyle->{Directive[Bold,17],Directive[Bold,17]}]

View Python Code using Matplotlib & Numpy

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import *

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

# input needs radians

theta = np.radians(60)

c, s = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

# rotation matrix

Q = np.array([[c, -s], [s, c]])

# array of points

points = np.array([[0, 1],

[5, 1],

[2, 3],

[0, 1]])

# array of rotated points

points2 = np.array([np.matmul(Q,i) for i in points])

print("Original triangle(blue)\n",points)

print("Rotation matrix\n",Q)

print("Rotated triangle(orange)\n",points2)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(points[:,0], points[:,1])

ax.plot(points2[:,0], points2[:,1])

ax.grid(True, which='both')

ax.axhline(y = 0, color = 'k')

ax.axvline(x = 0, color = 'k')

Example 5

The function “RotationMatrix[angle,vector]” can be used to create a rotation matrix create ![]() that is a rotation around a particular vector. You can use two- or three-dimensional graphics objects to visualize the effect of the rotation matrices. For example, in the following code, a rotation matrix

that is a rotation around a particular vector. You can use two- or three-dimensional graphics objects to visualize the effect of the rotation matrices. For example, in the following code, a rotation matrix ![]() with an angle of 60 degrees around the vector

with an angle of 60 degrees around the vector ![]() is first defined. Then a unit cube is created and transformed by a geometric transformation of the original cube.

is first defined. Then a unit cube is created and transformed by a geometric transformation of the original cube.

View Mathematica Code

thx = 60 Degree

Qx = RotationMatrix[thx, {1, 0, 0}];

c = Cuboid[{0, 0, 0}, {1, 1, 1}];

c1 = GeometricTransformation[c, Qx]

(*Viewing the two objects using the default graphics formatting*)

Graphics3D[{c, , c1}, Axes -> True, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

(*Viewing the two objects using a specific formatting*)

Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[.3, 0.4], Specularity[White, 2],

EdgeForm[Thickness[0.005]], c, Specularity[White, 6],

EdgeForm[Thickness[0.01]], c1}, Axes -> True,

AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}, Lighting -> "Neutral",

AxesStyle -> {Directive[Bold, 13], Directive[Bold, 13],

Directive[Bold, 13]}]

View Python Code using Matplotlib & Numpy

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

%matplotlib notebook

theta = np.radians(60)

c, s = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

# rotation on x axis

Q = np.array([[1, 0, 0],

[0, c, -s],

[0, s, c]])

# points for cube

points = np.array([[0, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1]])

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# plot surfaces and edges of the cube

r = [0,1]

# X = [[0,1],[0,1]]

# Y = [[0 0],[1 1]]

X, Y = np.meshgrid(r, r)

one = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)

zero = np.zeros(4).reshape(2, 2)

# display surface

ax.plot_surface(X,Y,one, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

ax.plot_surface(X,Y,zero, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

ax.plot_surface(X,zero,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

ax.plot_surface(X,one,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

ax.plot_surface(one,X,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

ax.plot_surface(zero,X,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "black")

# display outline

ax.plot_wireframe(X,Y,one, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

ax.plot_wireframe(X,Y,zero, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

ax.plot_wireframe(X,zero,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

ax.plot_wireframe(X,one,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

ax.plot_wireframe(one,X,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

ax.plot_wireframe(zero,X,Y, alpha = 0.5, color = "white")

# plot points of cube

ax.scatter3D(points[:, 0], points[:, 1], points[:, 2], color = "black")

# rotation of cube on x axis

points2 = np.matmul(Q,points[0])

def rotFrame(X,Y,Z):

temp = np.array([[X[i][j], Y[i][j], Z[i][j]] for i in range(X.shape[0]) for j in range(X.shape[1])])

out = np.array([np.matmul(Q,i) for i in temp])

# edit shape into 2 x 2

_X = np.array([out[:,0]]).reshape(2,2)

_Y = np.array([out[:,1]]).reshape(2,2)

_Z = np.array([out[:,2]]).reshape(2,2)

ax.plot_wireframe(_X,_Y,_Z, alpha=0.5,color="black")

ax.plot_surface(_X,_Y,_Z, alpha=0.5,color = "red")

rotFrame(X,Y,one)

rotFrame(X,Y,zero)

rotFrame(X,zero,Y)

rotFrame(X,one,Y)

rotFrame(one,X,Y)

rotFrame(zero,X,Y)

# rotate points

points2 = np.array([np.matmul(Q,i) for i in points])

# plot points

ax.scatter3D(points2[:, 0], points2[:, 1], points2[:, 2],color = "red")

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.set_zlabel('Z')

plt.show()

print("Cube points(blue)\n", points)

print("Rotation matrix on x axis\n",Q)

print("Rotated cube points(red)\n", points2)

Example 6

In the following code, the rotation matrices ![]() , and

, and ![]() defined as rotations around

defined as rotations around ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively, are created. A cuboid is then defined with opposite corners at

, respectively, are created. A cuboid is then defined with opposite corners at ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The function “Manipulate[]” is used to view the cuboid before and after applying the rotations

. The function “Manipulate[]” is used to view the cuboid before and after applying the rotations ![]() (blue cuboid) and

(blue cuboid) and ![]() (red cuboid). Copy and paste the code into your Mathematica software, and move the sliders to change the values of the rotation angles. The order of consecutive rotations is important. The application of

(red cuboid). Copy and paste the code into your Mathematica software, and move the sliders to change the values of the rotation angles. The order of consecutive rotations is important. The application of ![]() on a vector is equivalent to rotating the vector first by

on a vector is equivalent to rotating the vector first by ![]() , then by

, then by ![]() and finally by

and finally by ![]() . The resulting vector is different if

. The resulting vector is different if ![]() is applied.

is applied.

View Mathematica Code

Manipulate[Qx = RotationMatrix[thx, {1, 0, 0}];

Qy = RotationMatrix[thy, {0, 1, 0}];

Qz = RotationMatrix[thz, {0, 0, 1}];

c = Cuboid[{0, 0, 0}, {3, 2, 1}];

c1 = GeometricTransformation[c, Qx.Qy.Qz];

c2 = GeometricTransformation[c, Qz.Qy.Qx];

Graphics3D[{c, {Blue, c1}, {Red, c2}}, AxesStyle -> {Directive[Bold, 13], Directive[Bold, 13], Directive[Bold, 13]}, AxesLabel -> {"x", "y", "z"}, Axes -> True, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}], {thx, 0, 2 Pi}, {thy, 0, 2 Pi}, {thz, 0, 2 Pi}]

View Python Code using Matplotlib & Numpy

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.widgets import Slider

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

%matplotlib notebook

class plot3dCube(object):

def __init__(self, origin, length, color):

# origin[x,y,z], length[Lx,Ly,Lz],

# color[original[surface & point, edge], Qxyz[surface & point, edge], Qzxy[surface & point, edge]

Lx,Ly,Lz = length

x1,y1,z1 = origin

origin1 = x2,y2,z2 = [length[i]+origin[i] for i in range(3)]

# for A as X,Y,Z

# A_1212 uses [[x1, x2][x1,x2]]

# A_1122 is just X_1.T

# A_1111 all x1

# A_2222 all x2

r = [x1, x2]

X_1212 = np.array([r,r])

X_1111 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*x1

X_2222 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*x2

r = [y1, y2]

Y_1212, Y_1122 = np.meshgrid(r, r)

Y_1111 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*y1

Y_2222 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*y2

r = [z1, z2]

Z_1122 = np.array([r,r]).transpose()

Z_1111 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*z1

Z_2222 = np.ones(4).reshape(2, 2)*z2

# points of the cube

self.points = np.array([[x1, y1, z1],

[x2, y1, z1],

[x2, y2, z1],

[x1, y2, z1],

[x1, y1, z2],

[x2, y1, z2],

[x2, y2, z2],

[x1, y2, z2]])

# square points for surface, edges

self.sqrP = [[X_1212,Y_1122,Z_1111],[X_1212,Y_1122,Z_2222],

[X_1212,Y_1111,Z_1122],[X_1212,Y_2222,Z_1122],

[X_1111,Y_1212,Z_1122],[X_2222,Y_1212,Z_1122]]

# create plot figure

self.fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6,7))

self.ax = self.fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# range of axis

axis = origin+origin1

# get abolsute for each axis length

axis = [abs(i) for i in axis]

# get two highes axis lengths

for i in range(len(axis)-2):

axis.remove(min(axis))

# pythagorean theorem

l = np.sqrt(sum([i**2 for i in axis]))

self.ax.set_xlim3d(-l, l)

self.ax.set_ylim3d(-l, l)

self.ax.set_zlim3d(-l, l)

self.ax.set_xlabel('X')

self.ax.set_ylabel('Y')

self.ax.set_zlabel('Z')

# surface frame and edge variable names

self.s = ["self.surfacex","self.surfacez"]

self.e = ["self.edgex","self.edgez"]

# set color

self.ogColor, self.QxQyQzColor, self.QzQyQxColor = color

# Construct plot, surfaces and edges

# plot initial points

# black is original, does not move

self.sc = self.ax.scatter3D(self.points[:,0],self.points[:,1], self.points[:,2],color = self.ogColor[0])

# blue is Q = Qx*Qy*Qz

self.scx = self.ax.scatter3D(self.points[:,0],self.points[:,1], self.points[:,2], color = self.QxQyQzColor[0] )

# red is Q = Qz*Qy*Qx

self.scz = self.ax.scatter3D(self.points[:,0],self.points[:,1], self.points[:,2],color = self.QzQyQxColor[0])

# plot surface and edges

# Original cube(does not move)

self.color = self.ogColor

# dictionary of surfaces and edges

self.dFrm = {}

# surface variable name

surface = "self.surface"

# edge variable name

edge = "self.edge"

# original plot

for i in range(len(self.sqrP)):

# number

n = str(i)

self.dFrm[surface+n], self.dFrm[edge+n] = self.initFrame(self.sqrP[i][:])

for i in range(len(self.s)):

# QxQyQz plot

if(i == 0):

self.color = self.QxQyQzColor

# QzQyQx plot

else:

self.color = self.QzQyQxColor

surface = self.s[i]

edge = self.e[i]

# generate each surface and edge

for j in range(len(self.sqrP)):

n = str(j)

self.dFrm[surface+n], self.dFrm[edge+n] = self.initFrame(self.sqrP[j][:])

# slider plot

# adjust plot

plt.subplots_adjust(left = 0.1, bottom = 0.45)

# input the position of sliders

xSlider = plt.axes([0.2,0.2,0.5,0.03])

ySlider = plt.axes([0.2,0.15,0.5,0.03])

zSlider = plt.axes([0.2,0.1,0.5,0.03])

xSlider.set_xticks(np.array([90,180,270]), minor = True)

ySlider.set_xticks(np.array([90,180,270]), minor = True)

zSlider.set_xticks(np.array([90,180,270]), minor = True)

# input values and update graph

self.slider1 = Slider(xSlider, 'x angle', 0, 360, valinit = 0, valstep = 1)

self.slider2 = Slider(ySlider, 'y angle', 0, 360, valinit = 0, valstep = 1)

self.slider3 = Slider(zSlider, 'z angle', 0, 360, valinit = 0, valstep = 1)

# updates the graph when input is changes

self.slider1.on_changed(self.updateGraph)

self.slider2.on_changed(self.updateGraph)

self.slider3.on_changed(self.updateGraph)

# determins the rotation matricies from inputed angles

def setMatrix(self, x, y, z):

xtheta = np.radians(x)

ytheta = np.radians(y)

ztheta = np.radians(z)

# cos sin values

cx, sx = np.cos(xtheta), np.sin(xtheta)

cy, sy = np.cos(ytheta), np.sin(ytheta)

cz, sz = np.cos(ztheta), np.sin(ztheta)

# x rotation matrix

self.Qx = np.array([[1, 0, 0],

[0, cx, -sx],

[0, sx, cx]])

# y rotation matrix

self.Qy = np.array([[cy, 0, sy],

[0, 1, 0],

[-sy, 0, cy]])

# z rotation matrix

self.Qz = np.array([[cz, -sz, 0],

[sz, cz, 0],

[0, 0, 1]])

# QxQyQz Matrix

self.QxQyQz = self.Qx@self.Qy@self.Qz

# QzQyQx Matrix

self.QzQyQx = self.Qz@self.Qy@self.Qx

# When you first draw the frame and edges

def initFrame(self, sqrP):

surface = self.ax.plot_surface(sqrP[0],sqrP[1],sqrP[2],alpha=0.5,color=self.color[0])

edge = self.ax.plot_wireframe(sqrP[0],sqrP[1],sqrP[2],alpha=0.5,color=self.color[1])

return surface, edge

# rotate matrix * original to get new surface and edges

def rotFrame(self, surface, edge, X, Y, Z):

#destory previous surfaces and edges

surface.remove()

edge.remove()

# X, Y, Z are a 2x2 matrix

# first convert the 3 2x2 matricies into a 1 x 3 vector

temp = np.array([[X[i][j], Y[i][j], Z[i][j]] for i in range(X.shape[0]) for j in range(X.shape[1])])

# QxQyQz plot

if(self.color == self.QxQyQzColor):

out = np.array([np.matmul(self.QxQyQz,i) for i in temp])

# QzQyQx plot

elif(self.color == self.QzQyQxColor):

out = np.array([np.matmul(self.QzQyQx,i) for i in temp])

# edit shape into 2 x 2

_X = np.array([out[:,0]]).reshape(2,2)

_Y = np.array([out[:,1]]).reshape(2,2)

_Z = np.array([out[:,2]]).reshape(2,2)

# plot surfaces and edges

surface = self.ax.plot_surface(_X,_Y,_Z, alpha = 0.5, color = self.color[0])

edge = self.ax.plot_wireframe(_X,_Y,_Z, alpha = 0.5, color = self.color[1])

return surface, edge

# creates the rotated frame, then deletes the old one and adds the new one

def rotFrames(self):

for i in range(len(self.s)):

# QxQyQz cube

if(i == 0):

self.color = self.QxQyQzColor

# QzQyQx cube

else:

self.color = self.QzQyQxColor

surface = self.s[i]

edge = self.e[i]

# destroy current surface and edge, new surface and edge

for j in range(6):

n = str(j)

self.dFrm[surface+n], self.dFrm[edge+n]= self.rotFrame(self.dFrm[surface+n],self.dFrm[edge+n],

self.sqrP[j][0],self.sqrP[j][1],self.sqrP[j][2])

plt.draw()

plt.pause(.01)

# rotates the points of the scatter plot

def rotPoints(self):

# QxQyQz points

self.points2 = np.array([np.matmul(self.QxQyQz,i) for i in self.points])

# QzQyQx points

self.points3 = np.array([np.matmul(self.QzQyQx,i) for i in self.points])

# plot points

# QxQyQz plot

self.scx._offsets3d = (self.points2[:, 0], self.points2[:, 1], self.points2[:, 2])

# QzQyQx plot

self.scz._offsets3d = (self.points3[:, 0], self.points3[:, 1], self.points3[:, 2])

def updateGraph(self, event):

# change matrix

self.setMatrix(self.slider1.val,self.slider2.val,self.slider3.val)

# print points

self.rotPoints()

# print surfaces and edges

self.rotFrames()

# main function

# NOTE: spamming the inputs will freeze the plot

p = plot3dCube([0,0,0], [3,2,1],[["black","white"],["blue","blue"],["red","red"]])

#genInput()

Example 7

In the following code, two reflection matrices are created using the “ReflectionMatrix[vector]” function. Reflection is applied across the plane perpendicular to the vector specified. The blue and red triangles are reflections across the planes passing through the origin and perpendicular to the blue and red arrow directions, respectively.

View Mathematica Code

Q2=ReflectionMatrix[{1,1}]

Points={{0,1},{5,1},{2,3},{0,1}};

Points1=Table[Q1.Points[[i]],{i,1,4}];

Points2=Table[Q2.Points[[i]],{i,1,4}];

L1=Arrow[{{-5,0},{5,0}}]

L2=Arrow[{{-5,-5},{5,5}}]

c=Polygon[Points];

c1=Polygon[Points1];

c2=Polygon[Points2];

(*In gray tones*)

Graphics[{c,{GrayLevel[0.2],c1},{Arrowheads[{-.1,.1}],{GrayLevel[0.2],L1}},{Arrowheads[{-.1,.1}],{GrayLevel[0.5],L2}},{GrayLevel[0.5],c2}},Axes->True,AxesStyle->{Directive[Bold,13],Directive[Bold,13]},AxesOrigin->{0,0}]

(*In colour*)

Graphics[{c,{Blue,c1},{Arrowheads[{-.1,.1}],{Blue,L1}},{Arrowheads[{-.1,.1}],{Red,L2}},{Red,c2}},Axes->True,AxesOrigin->{0,0}]

View Python Code using Matplotlib & Numpy

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import *

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

# array of points

points = np.array([[0, 1],

[5, 1],

[2, 3],

[0, 1]])

print("Original triangle(black)\n",points)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.grid(True, which='both')

ax.axhline(y=0, color='k')

ax.axvline(x=0, color='k')

# relect points using the matrix

def refPlot(Q, color, out):

points2 = np.array([np.matmul(Q,i) for i in points])

ax.plot(points2[:,0], points2[:,1], color = color)

print("Reflected triange", out, points2)

# plot original points

ax.plot(points[:,0], points[:,1], color = "black")

# arrow lines

ax.arrow(-5,0,10,0, color = "blue",length_includes_head = True,head_width=.5, head_length=.5)

ax.arrow(-5,-5,10,10, color = "red",length_includes_head = True,head_width=.5, head_length=.5)

ax.arrow(5,0,-10,0, color = "blue",length_includes_head = True,head_width=.5, head_length=.5)

ax.arrow(5,5,-10,-10, color = "red",length_includes_head = True,head_width=.5, head_length=.5)

# plot reflected points

# matrix for reflecting on the y axis

refPlot(np.array([[-1,0],[0,1]]), "blue","on y axis(blue)\n")

# matrix for x = y

refPlot(np.array([[0,-1],[-1,0]]),"red","for x = y(red)\n")

Problems

- Show that a matrix

is not invertible if and only if 0 is an eigenvalue for

is not invertible if and only if 0 is an eigenvalue for  . In this case, what can you say about the set

. In this case, what can you say about the set  .

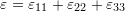

. - Find the determinant, the eigenvalues, and the eigenvectors of the following matrices. If a matrix is not invertible, then find its kernel. If a matrix is invertible, then, find its inverse:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \left(\begin{matrix}1&1\\-1&-1\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}1&1\\0&-1\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}5&0&0\\0&2&-1\\1&2&5\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}5&0&0\\0&2&-1\\10&2&-1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-544a384e8693ba9596c430f47cd43423_l3.png)

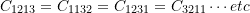

- Repeat the previous question for the following matrices:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \left(\begin{matrix}3&2&1\\4&6&5\\3&8&4\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}1&0&0\\0&2&-1\\1&2&5\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}1&0&0\\0&-2&-1\\5&2&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-622adf40667c35820a2bc94ce4a070b8_l3.png)

- Consider the vectors

, and

, and  . Find the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors. Also, find the volume of the parallelepiped formed when the three vectors are linearly mapped using the matrices

. Find the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors. Also, find the volume of the parallelepiped formed when the three vectors are linearly mapped using the matrices  , and

, and  defined below. Comment on the results.

defined below. Comment on the results.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M_a=\left(\begin{matrix}1.1&0.1&0\\0&0.9&0\\0&0&0.9\end{matrix}\right)\qquad M_b=\left(\begin{matrix}0&1.1&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ecdc9f51ae3838020a48d3a0f7ff39e5_l3.png)

- Consider a parallelepiped with edges

, and

, and  where

where  , and

, and  . Determine the new volume of the parallelpiped after a transformation of the space by the matrix

. Determine the new volume of the parallelpiped after a transformation of the space by the matrix  :

:

Comment on the sign of the resulting volume.![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}3&2&1\\0&2&1\\-1&-1&-1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-526fe05c6fee1bd363f624289c0545cb_l3.png)

-

Chose a value for

in the following matrices so that each matrix is not invertible. Then, find the kernel in each case:

in the following matrices so that each matrix is not invertible. Then, find the kernel in each case:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M_a=\left(\begin{matrix}M_{11}&5&5\\-3&5&-1\\0&2&-1\end{matrix}\right)\qquad M_b=\left(\begin{matrix}M_{11}&2&3&1\\-1&-2&1&-2\\1&3&1&-5\\5&2&1&7\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-16fd84236e7493705f377935c12229a9_l3.png)

- Use Mathematica Software to draw a two-dimensional polygon with five sides, and then use the table command to create 10 copies of the polygon rotated with an angle

between each copy. Finally, use the graphics command to view the 10 polygons you drew.

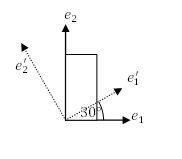

between each copy. Finally, use the graphics command to view the 10 polygons you drew. - The shown rectangle has a length of 2 units and height of 4 units. Find the coordinates of its vertices in the orthonormal basis set

. Find the coordinates of the vertices in the coordinate system defined by the basis set

. Find the coordinates of the vertices in the coordinate system defined by the basis set  .

.

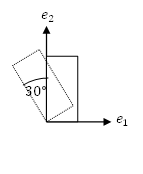

- The shown rectangle has a length of 2 units and height of 4 units. Find the coordinates of its vertices if the rectangle is rotated counterclockwise by the angle shown in the figure. Comment on the difference between the linear mapping used in this problem and that used in the previous problem.

- Verify that the following matrix is an orthogonal matrix, and specify whether it is a rotation or a reflection.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Q=\left(\begin{matrix}\frac{3}{4}&-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}&\frac{1}{2}\\\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}&\frac{5}{8}&-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\\-\frac{1}{8}&\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}&\frac{3}{4}\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7897ec0eb210fe421c3ae8241c9cc534_l3.png)

- Find the components

, and

, and  so that the following is a rotation matrix:

so that the following is a rotation matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q=\left(\begin{matrix}Q_{11}&Q_{12}&Q_{13}\\\frac{3}{8}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}&\frac{3}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{8}&-\frac{1}{4}\\\frac{1}{4}-\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}&\frac{3}{8}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}&\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8ae7ade3de456224ab417eb128325a04_l3.png)

- Find the components

, and

, and  so that the following is a reflection matrix:

so that the following is a reflection matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q=\left(\begin{matrix}Q_{11}&Q_{12}&Q_{13}\\\frac{3}{8}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}&\frac{3}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{8}&-\frac{1}{4}\\\frac{1}{4}-\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}&\frac{3}{8}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}&\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\end{matrix}\right)\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-58d8883348b2c4f2e2c7d3cf52b0c98e_l3.png)

- Find two possible combinations for the missing components in

so that it is a rotation matrix:

so that it is a rotation matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q=\left(\begin{matrix}0.1&0.2&Q_{13}\\0.1&Q_{22}&Q_{23}\\Q_{31}&Q_{32}&Q_{33}\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-04fec6535c46af2c97be1c5cece7d81d_l3.png)

- Find two possible combinations for the missing components in

so that it is an orthogonal matrix associated with reflection:

so that it is an orthogonal matrix associated with reflection:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Q=\left(\begin{matrix}0.1&0.2&Q_{13}\\0.1&Q_{22}&Q_{23}\\Q_{31}&Q_{32}&Q_{33}\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5c95da96d1d257d2c924d695b8bd687a_l3.png)

-

Consider the orthonormal basis set

and the matrix

and the matrix  :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}1&5&-2\\2&2&3\\-5&2&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3557766bbea38ab3ca8a531cc68570d3_l3.png)

- Let

. Verify that

. Verify that  and find the vector

and find the vector  that is orthogonal to both

that is orthogonal to both  , and

, and  . Find a new orthonormal basis set

. Find a new orthonormal basis set  using the normalized vectors of

using the normalized vectors of  , and

, and  .

. - Find the components of the matrix

in the new orthonormal basis set

in the new orthonormal basis set  .

. - Find the three invariants of

and

and  and verify that they are equal.

and verify that they are equal. - Find the eigenvalues of

and

and  and verify that they are equal.

and verify that they are equal. - Find the components of the eigenvectors of

and the eigenvectors of

and the eigenvectors of  and comment on whether they are the same vectors or not.

and comment on whether they are the same vectors or not.

- Let

- Repeat the previous question with

, and:

, and:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}-2&5&1\\3&2&2\\1&2&-5\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6110096a0b7051048d520cb5a69d4af7_l3.png)

- Consider the orthonormal basis set

and the matrix

and the matrix  :

:

If the orthonormal basis set![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ M=\left(\begin{matrix}3&0&0\\0&2&1\\0&0&4\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bc7e2e90033a41a54e06bc4211878058_l3.png)

is used as the coordinate system, find the components of

is used as the coordinate system, find the components of  in the new coordinate system.

in the new coordinate system.

- Consider the symmetric matrix

:

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ S=\left(\begin{matrix}1&0&-2\\0&2&0\\-2&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c8efb94295a6904e4f04045bec5a32ba_l3.png)

- Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

.

. - Find a new coordinate system

such that the matrix of components

such that the matrix of components  in the new coordinate system is a diagonal matrix.

in the new coordinate system is a diagonal matrix.

- Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

- Identify the positive definite and semi-positive definite symmetric matrices in the following:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \left(\begin{matrix}1&0&-2\\0&2&0\\-2&0&1\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}1&0&2\\0&2&0\\2&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \qquad \left(\begin{matrix}1&0&-2\\0&2&0\\-2&0&0\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}-1&0&-2\\0&2&0\\-2&0&1\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-07466c4e7d7e0208e454eaf8e8f49343_l3.png)

- Find the missing values in the components of the orthogonal matrix

so that it represents a change of basis while maintaining the proper orientation.

so that it represents a change of basis while maintaining the proper orientation.

Then, find the components of the identity matrix when a coordinate transformation using![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \left(\begin{matrix}\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\\?&?&?\\0&?&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5ca8bfc135bfebd5b28de874efc1705e_l3.png)

is applied. Comment on the results.

is applied. Comment on the results. - Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the following symmetric matrices and then perform the diagonalization process for each.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \left(\begin{matrix}11&4&0\\4&5&0\\0&0&7\end{matrix}\right)\qquad \left(\begin{matrix}7&0&-2\\0&5&0\\-2&0&4\end{matrix}\right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-db66c7ebb7d828d1509a1ab14ed57948_l3.png)

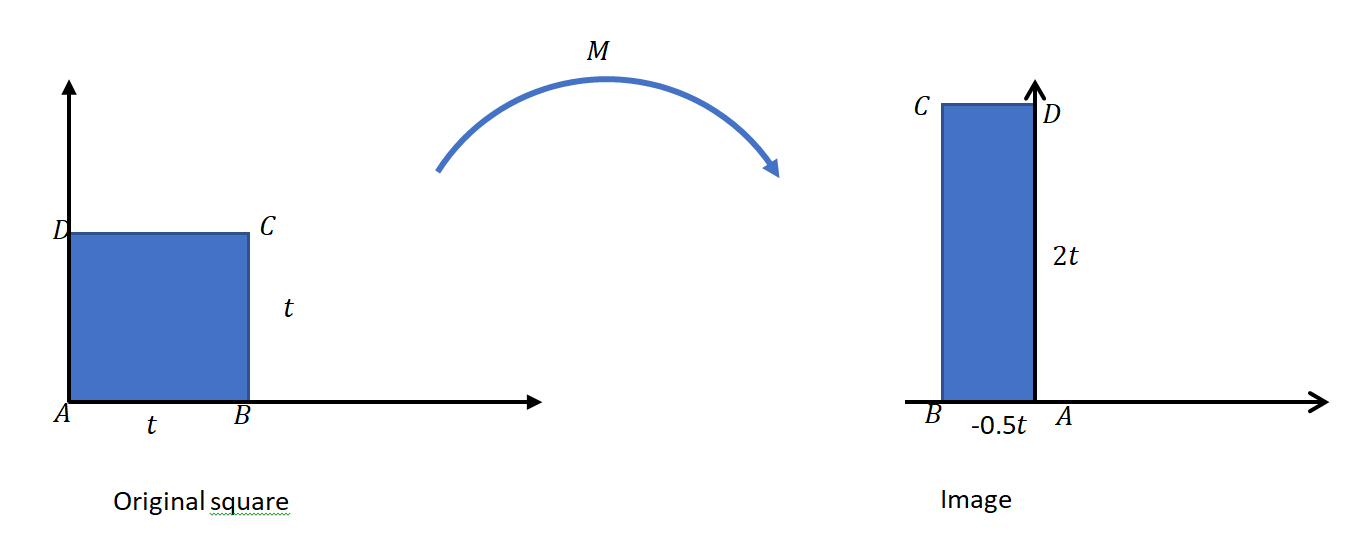

- The figure below shows a square with dimension

. Determine the transformation matrix

. Determine the transformation matrix  applied to the object to produce the image shown.

applied to the object to produce the image shown.

- Let

, and

, and  be three vectors that are linearly independent. Using the properties of the dot product, construct an orthonormal basis set as a function of

be three vectors that are linearly independent. Using the properties of the dot product, construct an orthonormal basis set as a function of  , and

, and  . (The construction is referred to as: Gram-Schmidt Process)

. (The construction is referred to as: Gram-Schmidt Process) - Let

. Find an example of a matrix

. Find an example of a matrix  such that

such that  . Then, show that if

. Then, show that if  is a rotation matrix, then

is a rotation matrix, then  .

. - Using Einstein summation convention, and assuming that the underlying space is the Euclidean space

, show that the following relations hold true for the Kronecker Delta

, show that the following relations hold true for the Kronecker Delta  and the alternator

and the alternator  :

:

- Write the following expressions out in full assuming that the underlying space is the Euclidean space

:

:

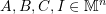

- Write the following expressions in a compact form using index notation and the Einstein summation convention:

-

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split}c_{11}x_1+c_{12}x_2+c_{13}x_3 & =d_1\\c_{21}x_1+c_{22}x_2+c_{23}x_3&=d_2 \\ c_{31}x_1+c_{32}x_2+c_{33}x_3&=d_3\end{split} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5df89d4ff36ea301896e1ee2eeb34b9d_l3.png)

.

.- In the following expressions assume that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \sigma_{11}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{11}+\lambda\varepsilon\\ \sigma_{22}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{22}+\lambda\varepsilon\\ \sigma_{33}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{33}+\lambda\varepsilon\\ \sigma_{12}=\sigma_{21}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{12}=2\mu\varepsilon_{21}\\ \sigma_{13}=\sigma_{31}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{13}=2\mu\varepsilon_{31}\\ \sigma_{32}=\sigma_{23}&=2\mu\varepsilon_{23}=2\mu\varepsilon_{32} \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-452e7ead50a2095225412b6badc39794_l3.png)

-

- Show that symmetric and antisymmetric matrices stay symmetric and antisymmetric, respectively, under any orthogonal coordinate transformation.

- Using the definitions of symmetric and antisymmetric tensors without reference to components.

- Using the component forms of symmetric and antisymmetric matrices.

- In a three dimensional Euclidean vector space, how many independent components will the following tensors have:

- A “completely symmetric” third order tensor.

- A “completely symmetric” fourth order tensor.

is a completely symmetric fourth order tensor, then:

is a completely symmetric fourth order tensor, then:  .

.

- Show that if

and

and  are symmetric matrices, then

are symmetric matrices, then  is not necessarily a symmetric matrix. (Hint: Find a counter example). On the other hand, show that if

is not necessarily a symmetric matrix. (Hint: Find a counter example). On the other hand, show that if  and

and  are symmetric matrices that have the same eigenvectors (also called “coaxial”), then

are symmetric matrices that have the same eigenvectors (also called “coaxial”), then  and

and  are symmetric.

are symmetric. - Show that if

is a symmetric matrix, then

is a symmetric matrix, then  , the matrix

, the matrix  is symmetric.

is symmetric. - Let

and

and  is the identity matrix. Using the algebraic structure of matrices, show that if

is the identity matrix. Using the algebraic structure of matrices, show that if  and

and  , then

, then  . The matrix

. The matrix  is referred to as the inverse of

is referred to as the inverse of  and is denoted

and is denoted  .

. - Let

be a symmetric matrix. Let

be a symmetric matrix. Let  and

and  be the minimum and maximum eigenvalues of

be the minimum and maximum eigenvalues of  . Show that

. Show that  . (The quantity

. (The quantity  is referred to as the Rayleigh Quotient)

is referred to as the Rayleigh Quotient) - Let

. Let

. Let  be an invertible symmetric matrix. Show the following:

be an invertible symmetric matrix. Show the following:

is symmetric.

is symmetric.

- Let

be a symmetric matrix. Let

be a symmetric matrix. Let  be another matrix. Find the restriction on

be another matrix. Find the restriction on  to ensure that the matrix

to ensure that the matrix  is symmetric, i.e., that

is symmetric, i.e., that  . (Hint: in a coordinate system of the eigenvectors of

. (Hint: in a coordinate system of the eigenvectors of  the ratios between the off diagonal components of

the ratios between the off diagonal components of  is equal to the ratios between the corresponding eigenvalues of

is equal to the ratios between the corresponding eigenvalues of  )

) -

As will be discussed later, the stress at a point can be described as a symmetric matrix with the following form:

Assume a change of coordinates described by the following rotation matrix![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \sigma=\begin{pmatrix}\sigma_{11}&\sigma_{12}&\sigma_{13}\\\sigma_{12}&\sigma_{22}&\sigma_{23}\\\sigma_{13}&\sigma_{23}&\sigma_{33}\end{pmatrix} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0e21b789bad9ff763a907b7a6b338b82_l3.png)

In the new coordinate system, the comonents of![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q=\begin{pmatrix}\cos{(\theta)}&\sin{(\theta)}&0\\-\sin{(\theta)}&\cos{(\theta)}&0\\0&0&1\end{pmatrix} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d4f79e5c4a72a30b2d23d0e97d1eb901_l3.png)

will have the following form:

will have the following form:

If a vector representation of the stress is adopted as follows:![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma=Q \sigma Q^T\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7a2cc24dd1c0274823cbc1beeb3338ba_l3.png)

Then, show that the components of the vector after transformation are given by:![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \sigma_v=\begin{pmatrix}\sigma_{11}\\\sigma_{22}\\\sigma_{33}\\\sigma_{12}\\\sigma_{13}\\\sigma_{23}\end{pmatrix} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ec40c9daa7a75e7c26df47a3b79cba9e_l3.png)

where![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma_v'=Q_v \sigma_v\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-da7fcb152c08895605b177fb988c3418_l3.png)

has the following form:

has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ Q_v= \left( \begin{array}{cccccc} \cos ^2(\theta) & \sin ^2(\theta) & 0 & \sin (2 \theta) & 0 & 0 \\ \sin ^2(\theta) & \cos ^2(\theta) & 0 & -\sin (2 \theta) & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -\frac{1}{2} \sin (2 \theta) & \frac{1}{2} \sin (2 \theta) & 0 & \cos (2 \theta) & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cos (\theta) & \sin (\theta) \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -\sin (\theta) & \cos (\theta) \\ \end{array} \right) \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cf0797cdd091134f545a18449efcaf17_l3.png)