Linear Elastic Materials: Plane Isotropic Linear Elastic Materials Constitutive Laws

Learning Outcomes

- Compare plane stress, plane strain, and axisymmetric states and provide physical examples of each.

- Recognize the conditions that lead to simplified relationships between stresses and strains.

- Describe and derive these simplified relationships.

- Compute the stresses and/or the strain in the plane stress, plane strain, and axisymmetric states.

In many solid mechanics problems, it is possible, due to loading and geometry symmetries, to simplify particular problems to be solved in ![]() rather than

rather than ![]() . In such cases, the matrix of elastic moduli shown in Equations 6 and 7 can be reduced from a

. In such cases, the matrix of elastic moduli shown in Equations 6 and 7 can be reduced from a ![]() matrix to a

matrix to a ![]() or

or ![]() matrix that accounts for such symmetries. In the following, the material is assumed to be isotropic linear elastic and the measure of strain is the infinitesimal strain tensor.

matrix that accounts for such symmetries. In the following, the material is assumed to be isotropic linear elastic and the measure of strain is the infinitesimal strain tensor.

Plane Stress

The plane stress assumption is used when the non-zero stress components are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Usually, this assumption is used for situations when a material is allowed to freely contract and/or expand in one direction (called the thickness direction) while the loads are applied only in the plane perpendicular to the thickness direction. In this situation, the stress matrix has the following form:

. Usually, this assumption is used for situations when a material is allowed to freely contract and/or expand in one direction (called the thickness direction) while the loads are applied only in the plane perpendicular to the thickness direction. In this situation, the stress matrix has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} & 0 \\ \sigma_{12} & \sigma_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2f07c95e0fd4d4a1a4c015d2c1db08bb_l3.png)

Using Equation 6, ![]() and the strain matrix has the following form:

and the strain matrix has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\varepsilon = \begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{11} & \varepsilon_{12} & 0 \\ \varepsilon_{12} & \varepsilon_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \varepsilon_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-51a38dc59e54055fcb147ef24352f2f9_l3.png)

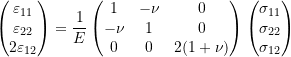

The relationship between the stress and strain components shown in Equation 6 can now be reduced to only account for the stresses that are not necessarily equal to zero:

(9)

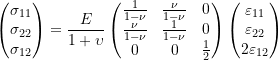

The inverse of this relationship has the following form:

(10)

In the plane stress assumption, the material is allowed to expand and contract freely in the third direction. The corresponding value of the axial strain in the thickness direction can be obtained using the equation:

![]()

Plane Strain

The plane strain assumption is used when the non-zero strain components are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Usually, this assumption is used for situations when a material is restrained from contracting or expanding in one direction (called the thickness direction). The loads are applied in the plane perpendicular to the thickness direction and a restraining stress is applied in the thickness direction. In this situation, the strain matrix has the following form:

. Usually, this assumption is used for situations when a material is restrained from contracting or expanding in one direction (called the thickness direction). The loads are applied in the plane perpendicular to the thickness direction and a restraining stress is applied in the thickness direction. In this situation, the strain matrix has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\varepsilon = \begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{11} & \varepsilon_{12} & 0 \\ \varepsilon_{12} & \varepsilon_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9d698cdcf1eed5f45dbbe110661339cf_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} & 0 \\ \sigma_{12} & \sigma_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sigma_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-53b1c7cfe71775e7fd53c5c486de181d_l3.png)

(11)

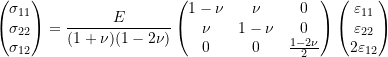

The inverse of this relationship has the following form:

(12)

In the plane strain assumption, the material is restrained from expanding or contracting in the third direction. The restraining axial stress in the thickness direction can be obtained using the equation:

![]()

Axisymmetry

Axisymmetry is used for modelling cylindrical shapes when the loads and boundary conditions are also cylindrical. By considering an cross section where ![]() is aligned with the axis of symmetry, the shear stresses

is aligned with the axis of symmetry, the shear stresses ![]() and

and ![]() can be assumed to be zero. In this situation, the stress matrix has the following form:

can be assumed to be zero. In this situation, the stress matrix has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} & 0 \\ \sigma_{12} & \sigma_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sigma_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0bc37d5da38aba1c862e598f393a14f2_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\varepsilon = \begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{11} & \varepsilon_{12} & 0 \\ \varepsilon_{12} & \varepsilon_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \varepsilon_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-51a38dc59e54055fcb147ef24352f2f9_l3.png)

The axisymmetry assumption leads to the following relationship between the displacement ![]() , the radius

, the radius ![]() and the strain component

and the strain component ![]() as follows:

as follows:

![]()

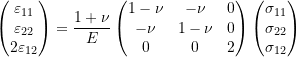

The relationship between the stress and strain components shown in Equation 6 can now be reduced to only account for the stresses that are not necessarily equal to zero:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{11} \\ \varepsilon_{22} \\ \varepsilon_{33} \\ 2\varepsilon_{12} \\ \end{pmatrix} = \frac{1}{E} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -\nu & -\nu & 0 \\ -\nu & 1 & -\nu & 0 \\ -\nu & -\nu & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 2(1+\nu) \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} \\ \sigma_{22} \\ \sigma_{33} \\ \sigma_{12} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5e3a8623edf7285d7f9db5712d4ee5e3_l3.png)

The inverse of this relationship has the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} \\ \sigma_{22} \\ \sigma_{33} \\ \sigma_{12} \\ \end{pmatrix} = \frac{E}{(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)} \begin{pmatrix} 1-\nu & \nu & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & 1-\nu & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & \nu & 1-\nu & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \frac{1-2\nu}{2} \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{11} \\ \varepsilon_{22} \\ \varepsilon_{33} \\ 2\varepsilon_{12} \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-fd0f082b9e4449c17113b51ebf1f7b02_l3.png)