Displacement and Strain: Description of Motion and Simple Examples

Learning Outcomes

- Define the mathematical description of motion as a mathematical function that relates the material points of an object in an “undeformed” or “pre-deformed” state to its “deformed” state.

- Identify the following examples of deformation functions: Rigid body displacement, rigid body rotation, rigid body motion, Uniform extension and contraction, Simple shear, pure shear.

Description of Motion

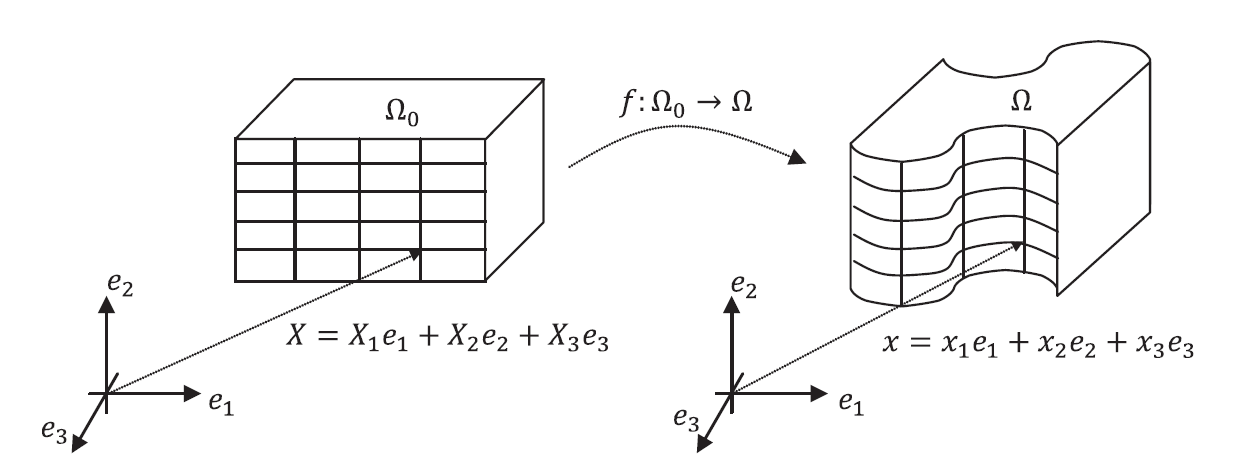

The geometry of a continuum body can be represented mathematically by “embedding” it in a Euclidean Vector Space ![]() where every material point in the body can be represented by a unique vector in the space. We denote the set of vectors corresponding to the material points by

where every material point in the body can be represented by a unique vector in the space. We denote the set of vectors corresponding to the material points by ![]() . The embedding is called a “configuration”. An analyst is usually interested in comparing a “deformed” configuration

. The embedding is called a “configuration”. An analyst is usually interested in comparing a “deformed” configuration ![]() with an “undeformed” or a “reference” configuration

with an “undeformed” or a “reference” configuration ![]() . Traditionally, elements of the deformed configuration are denoted by

. Traditionally, elements of the deformed configuration are denoted by ![]() while elements in the reference configuration are denoted by

while elements in the reference configuration are denoted by ![]() . The deformed configuration can be assumed to be a function

. The deformed configuration can be assumed to be a function ![]() such that

such that ![]() (Figure 1). In the majority of continuum mechanics applications, the following are the major restrictions on the possible choices of the position function

(Figure 1). In the majority of continuum mechanics applications, the following are the major restrictions on the possible choices of the position function ![]() .

.

-

First, we assume that the deformation between configurations preserves the distinction between material points, i.e., that material is not flattened out or lost during configuration. This restricts

to be bijective.

to be bijective. -

Second, we assume that material points don’t change their neighbours, i.e., no cracks or rearrangement of material points occur during deformation. This restricts

to be continuous.

to be continuous.

-

In most applications we add the third restriction of being “smooth” or “differentiable” on the possible choices for

. This ensures that straight lines on the reference configuration deform into smooth curves in the deformed configuration. This allows the calculation of derivatives and the definition of “strain”.

. This ensures that straight lines on the reference configuration deform into smooth curves in the deformed configuration. This allows the calculation of derivatives and the definition of “strain”.

The displacement function of the body (termed the displacement field) is denoted by the function ![]() such that:

such that:

![]()

is the set of vectors representing the reference configuration, while

is the set of vectors representing the reference configuration, while  is the set representing the deformed configuration

is the set representing the deformed configuration A geometric object is embedded in ![]() is the set of vectors representing the reference configuration, while

is the set of vectors representing the reference configuration, while![]() is the set representing the deformed configuration.

is the set representing the deformed configuration.

In the following section a few simple examples of deformations along with their position and displacement functions are presented.

Rigid Body Displacement

A rigid body displacement is represented by a constant displacement vector at every point. The new (deformed) position ![]() of every point is related to the old (reference) position

of every point is related to the old (reference) position ![]() as follows:

as follows:

![]()

where

![]()

is a constant vector. The displacement field at every point is the difference between the deformed and reference positions and is constant:

![]()

Change the components of the vector ![]() in the following tool to view its effect on the displacement of the cuboid.

in the following tool to view its effect on the displacement of the cuboid.

Rigid Body Rotation

A rigid body rotation is represented by a rotation matrix ![]() ( see Orthogonal Tensors ) such that the new (deformed) position

( see Orthogonal Tensors ) such that the new (deformed) position ![]() of every point is equal to the rotation matrix Q multiplied by the old (reference) position

of every point is equal to the rotation matrix Q multiplied by the old (reference) position ![]() as follows:

as follows:

![]()

The displacement field at every point is the difference between the deformed and reference positions:

![]()

Recall that any rotation matrix can be viewed as consecutive rotations around each of the basis vectors of the coordinate system. Clockwise rotations with angles ![]() around the basis vectors

around the basis vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are given by the following matrices

are given by the following matrices ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively:

, respectively:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q_a = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos(\theta_a) & \sin(\theta_a) \\ 0 & -\sin(\theta_a) & cos(\theta_a) \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-46ebe2f48f32f4c8bc9e1c2e56840059_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q_b = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\theta_b) & 0 & -\sin(\theta_b) \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \sin(\theta_b) & 0 & cos(\theta_b) \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-10a1dd7c28a043ae401cdaed74151699_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q_c = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\theta_c) & \sin(\theta_c) & 0 \\ -\sin(\theta_c) & \cos(\theta_c) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2cc684de65c0bcbfb483fc189c26689b_l3.png)

It is important to notice that the order of rotation changes the final position of the rotated object. The rotation matrix ![]() describes a rotation of

describes a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() followed by a rotation of

followed by a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() and finally a rotation of

and finally a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() . On the other hand, the rotation matrix

. On the other hand, the rotation matrix ![]() describes a rotation of

describes a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() followed by a rotation of

followed by a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() and finally a rotation of

and finally a rotation of ![]() around

around ![]() . In general:

. In general: ![]() . In the following example, the red box represents the original box after rotation around the basis vectors. Try it out: rotate the box 90 degrees around

. In the following example, the red box represents the original box after rotation around the basis vectors. Try it out: rotate the box 90 degrees around ![]() and then slowly rotate it around

and then slowly rotate it around ![]() . This order is applied to the image on the left. The order of rotation applied to the one on the right is reversed! Compare the two orders of rotation. The overall matrix of transformation is displayed at the bottom of each image.

. This order is applied to the image on the left. The order of rotation applied to the one on the right is reversed! Compare the two orders of rotation. The overall matrix of transformation is displayed at the bottom of each image.

Rigid Body Motion

A rigid body motion is a combination of both a rigid body displacement and a rigid body rotation such that the deformed position ![]() is function of the reference position

is function of the reference position ![]() as follows:

as follows:

![]()

where ![]() is a rotation matrix and

is a rotation matrix and ![]() is a vector representing the rigid body displacement. The displacement field can be expressed as:

is a vector representing the rigid body displacement. The displacement field can be expressed as:

![]()

can be written as follows:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} Q_{11} & Q_{12} & Q_{13} \\ Q_{21} & Q_{22} & Q_{23} \\ Q_{31} & Q_{32} & Q_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f66eac5e312aea04d5d610961816b35d_l3.png)

Note that in some numerical analysis software and tools, the above relationship adopts the following form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} Q_{11} & Q_{12} & Q_{13} & c_1 \\ Q_{21} & Q_{22} & Q_{23} & c_2 \\ Q_{31} & Q_{32} & Q_{33} & c_3 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-131b516902ea14d0e2a23e354b4ec755_l3.png)

Change the angles of rotation and the components of the vector ![]() in the following tool to see the effect on the final position of the cube.

in the following tool to see the effect on the final position of the cube.

Uniform Extension and Contraction

A uniform extension or contraction can be characterized by three positive parameters ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() that represent the ratios between the three vector components in the deformed configuration to the components in the reference configuration:

that represent the ratios between the three vector components in the deformed configuration to the components in the reference configuration:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} k_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & k_2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & k_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} k_1 X_1 \\ k_2 X_2 \\ k_3 X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-be27f5ea527b0cf431225d9aa1f1e86d_l3.png)

Note that the relationship can be written as a linear transformation ![]() where

where ![]() has the form:

has the form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M = \begin{pmatrix} k_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & k_2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & k_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a24d44e35cc1e8d5096450e54fc8bae0_l3.png)

In the following example, you can vary the values of ![]() ,

,

![]() ,and

,and ![]() to see the effect on the deformation of a cube. What values constitute compression and what values constitute tension? Also, what does it mean that the value of

to see the effect on the deformation of a cube. What values constitute compression and what values constitute tension? Also, what does it mean that the value of ![]() is equal to 1 or 0?

is equal to 1 or 0?

Simple Shear

The simple shear motion is described by a shearing angle along a certain direction and perpendicular to another direction. The following relationship describes a simple shear motion in which the planes parallel to the basis vectors ![]() and

and ![]() are sheared in the direction of

are sheared in the direction of ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta) & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} X_1 + \tan(\theta)X_2 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9591f864c60f173b2d725120ddacafaa_l3.png)

Note that the relationship can be written as a linear transformation

![]() where

where ![]() Note that the relationship can be written as a linear transformation has the form:

Note that the relationship can be written as a linear transformation has the form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta) & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-293e5801742c6046b0926e110d43a222_l3.png)

In the following example, change the values of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() in the matrix

in the matrix ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta_{xy}) & \tan(\theta_{xz}) \\ 0 & 1 & \tan(\theta_{yz}) \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-72d78d657c2b5d9d69f66602f010defd_l3.png)

and observe the effect on the deformation ![]() . The term simple shear applies to the deformations when only one of the angles

. The term simple shear applies to the deformations when only one of the angles ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() is non-zero.

is non-zero.

Pure Shear

The following relationship describes a pure shear motion with an angle ![]() in the plane of

in the plane of ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta/2) & 0 \\ \tan(\theta/2) & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} X_1 + \tan(\theta/2)X_2 \\ \tan(\theta/2)X_1 + X_2 \\ X_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b1f310d67b692a862fc736130b68c6f9_l3.png)

Note that the relationship can be written as a linear transformation ![]() where

where ![]() has the form:

has the form:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta/2) & 0 \\ \tan(\theta/2) & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8c83e144decf36c8c37fc9dc65063dac_l3.png)

The difference between pure shear and simple shear can be viewed in the following two dimensional example. Change the value of ![]() to see the deformation of a rectangle under pure shear (on the left) and under simple shear (on the right). The matrix

to see the deformation of a rectangle under pure shear (on the left) and under simple shear (on the right). The matrix ![]() in each case is given underneath the figure:

in each case is given underneath the figure:

In the following example, change the values of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() in the matrix

in the matrix ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \tan(\theta_{xy/2}) & \tan(\theta_{xz/2}) \\ \tan(\theta_{xy/2}) & 1 & \tan(\theta{yz/2}) \\ \tan(\theta_{xz/2}) & t\tan(\theta_{yz/2}) & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-df044d0460f9459a33da7c55e1de86c4_l3.png)

and observe the effect on the deformation ![]() . The term pure shear applies to the deformations when only one of the angles

. The term pure shear applies to the deformations when only one of the angles ![]() ,

, ![]() ,and

,and ![]() is non-zero.

is non-zero.

The definition of the displacement function is f(X) – X (the former X being a capital letter).

Dear Sir/Madam,

Thank you so much for your awesome eBook.

I have some confusion regarding the rotation angle in your example above. Does your example about the rotation angle follow the rule for clockwise and counterclockwise directions?

I have checked it and found that it may not follow this rule. Could you please check and clarify?

Thank you so much.

Best regards,

Tam

Which example?