Single Degree of Freedom Systems: Spring–Mass System Undergoing Vertical Vibrations

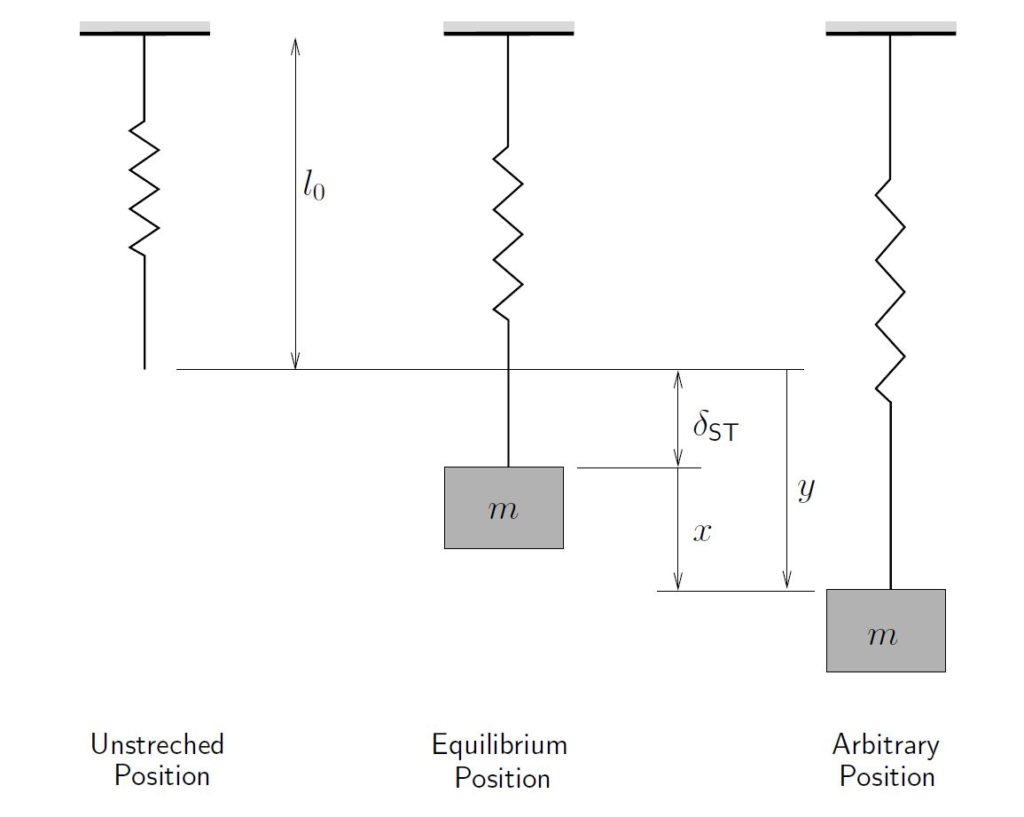

The simple spring–mass system we have considered so far has been assumed to be moving horizontally so that gravity does not play a role. We now consider the situation in which the mass is moving vertically as illustrated in Figure 2.6.

Here we will consider two coordinates: ![]() measured from the equilibrium position and

measured from the equilibrium position and ![]() measured from the unstretched length of the spring. Note that other coordinates could have been chosen as well, but these will serve to illustrate the important points. Before proceeding note that

measured from the unstretched length of the spring. Note that other coordinates could have been chosen as well, but these will serve to illustrate the important points. Before proceeding note that ![]() and

and ![]() are related by

are related by

(2.13) ![]()

so that

(2.14) ![]()

since ![]() is a constant determined from equilibrium considerations.

is a constant determined from equilibrium considerations.

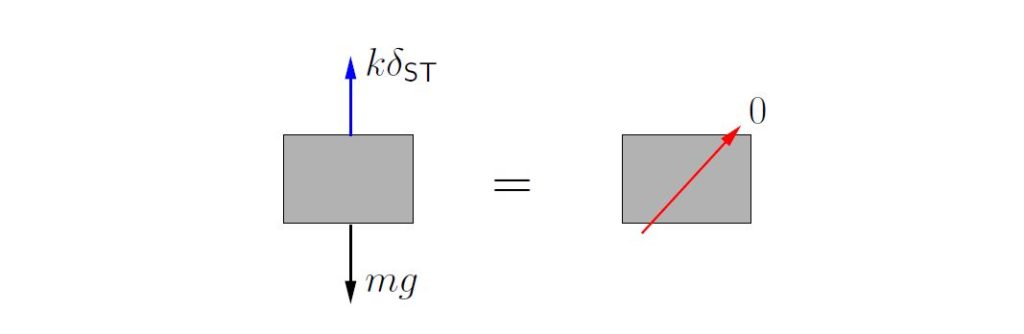

When the system is in equilibrium, the FBD/MAD in Figure 2.7 shows that

![]()

or

(2.15) ![]()

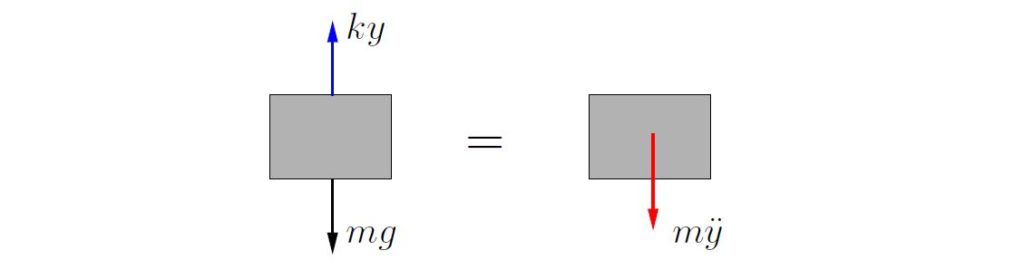

When the system is in motion, from the FBD/MAD in Figure 2.8 we see that (using ![]() as the coordinate)

as the coordinate)

![]()

so that

(2.16) ![]()

Equation 2.16 is a valid equation of motion but is not in standard form so does not have the same solution discussed previously. To obtain the standard form, we can use the results from 2.13 and 2.14

![]()

and using the equilibrium result 2.15 we get

![]()

which is now in the standard form. Note that when we use ![]() measured from the equilibrium position the equation of motion obtained is identical to that for the situation in which the mass moves horizontally as considered previously. This is true despite the fact that gravity now plays a significant role. The reason this works is that we are essentially ignoring the effect of gravity but at the same time, we also ignore the static equilibrium stretch in the spring. For example, the term

measured from the equilibrium position the equation of motion obtained is identical to that for the situation in which the mass moves horizontally as considered previously. This is true despite the fact that gravity now plays a significant role. The reason this works is that we are essentially ignoring the effect of gravity but at the same time, we also ignore the static equilibrium stretch in the spring. For example, the term ![]() does not represent the actual force in the spring in vertical vibrations as it does in the horizontal situation. In the vertical case,

does not represent the actual force in the spring in vertical vibrations as it does in the horizontal situation. In the vertical case, ![]() represents only the change in the spring force as the mass is displaced from the equilibrium position. The actual force in the spring will also include the equilibrium force in the spring (in this case the weight of the mass).

represents only the change in the spring force as the mass is displaced from the equilibrium position. The actual force in the spring will also include the equilibrium force in the spring (in this case the weight of the mass).

For this approach to work, we must ignore both the effect of gravity and the static stretch in the spring. If we ignore only one of these terms, we will get the wrong answer.

This concept also works if we use an energy approach. To see this, let us use ![]() as the coordinate again. This system is conservative so

as the coordinate again. This system is conservative so

![]()

In terms of ![]() the kinetic and potential energies are

the kinetic and potential energies are

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} T &= \frac{1}{2} m \dot{y}^2, \\[2mm] U &= \frac{1}{2} k y^2 - mgy, \end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-06f8cb662e32733f821638442fa09803_l3.png)

where the end of the unstretched spring has been chosen as our datum. The total energy is then

![]()

Differentiating with respect to time produces

![]()

![]()

which leads to the (non-standard) equation of motion obtained previously in 2.16

![]()

Alternatively, if we start with ![]() as our coordinate, the kinetic and potential energies become

as our coordinate, the kinetic and potential energies become

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} T &= \frac{1}{2} m \dot{x}^2, \\[2mm] U &= \frac{1}{2} k \bigl(x+\delta_{\text{ST}}\bigr)^2 - mg\bigl(x+\delta_{\text{ST}}\bigr), \end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b26918e69648dd844d63f275205c3b43_l3.png)

where the same datum has been selected. The total energy becomes

![]()

Differentiating with respect to time produces

![]()

or

![]()

which leads to the equation of motion

![]()

However using the equilibrium result 2.15, this again simplifies to

![]()

Once again, if we measure displacements from the equilibrium position and we ignore both the effect of gravity and the static equilibrium stretch in the spring, we arrive at the correct equation of motion. As illustrated above, if we do not make these assumptions, but account for everything in full detail, we eventually arrive at the same equation of motion. There are situations however where it may not be possible to obtain the equation of motion without starting with these assumptions (or without being given additional information).

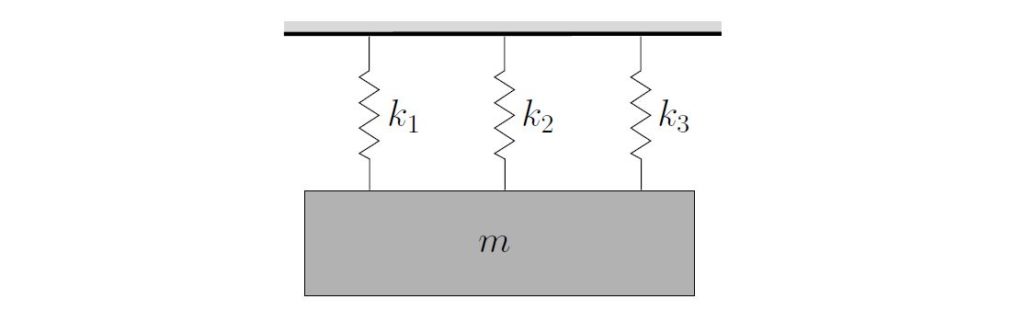

Consider the situation shown in Figure 2.9. Unless we are given more information, such as the unstretched length of each spring, we cannot determine the equilibrium stretch in each spring. One or more of the springs may be unloaded or even compressed. However, if we choose the displacement from the equilibrium position as the coordinate, we can simply ignore these static stretches in each of the springs (provided of course we also neglect the effect of gravity).

Finally for the system in Figure 2.8, note that if we do know the static stretch in the equilibrium position it is possible to determine the natural frequency directly. Starting with

![]()

we can see that

![]()

but from equilibrium considerations we have shown that

![]()

so that we get finally.

![]()

EXAMPLE

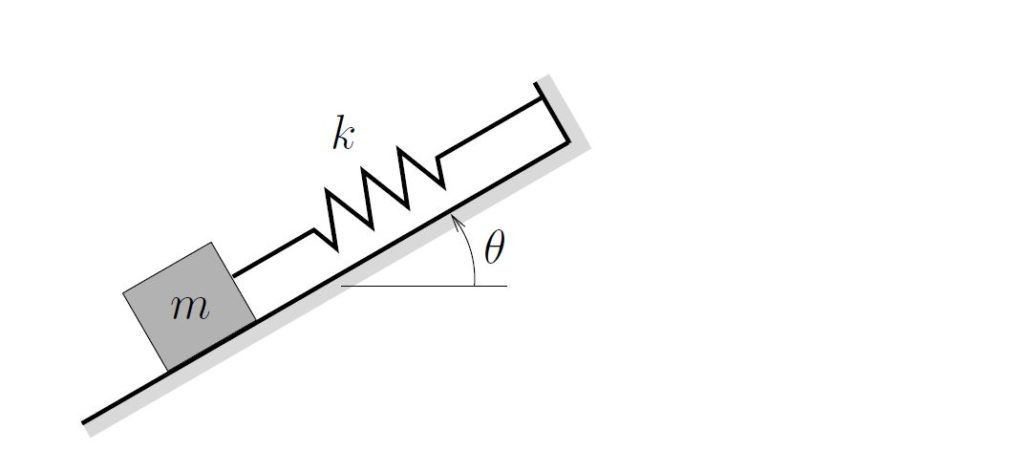

In the system shown below a mass is supported on a smooth incline by a linear spring. Determine the equation of motion and natural frequency for this system.

EXAMPLE

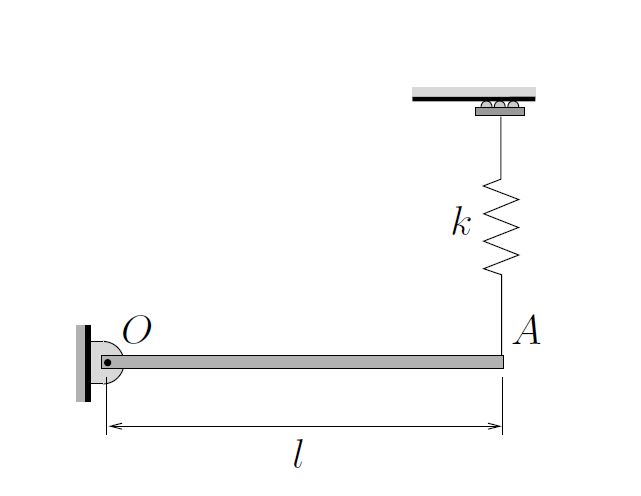

A thin uniform bar (length ![]() , mass

, mass ![]() ) is pinned at one end and is supported by a vertical linear spring at its other end. The bar is in equilibrium when it is in the horizontal position. Determine the equation of motion and natural frequency for small vibrations of the bar.

) is pinned at one end and is supported by a vertical linear spring at its other end. The bar is in equilibrium when it is in the horizontal position. Determine the equation of motion and natural frequency for small vibrations of the bar.

EXAMPLE

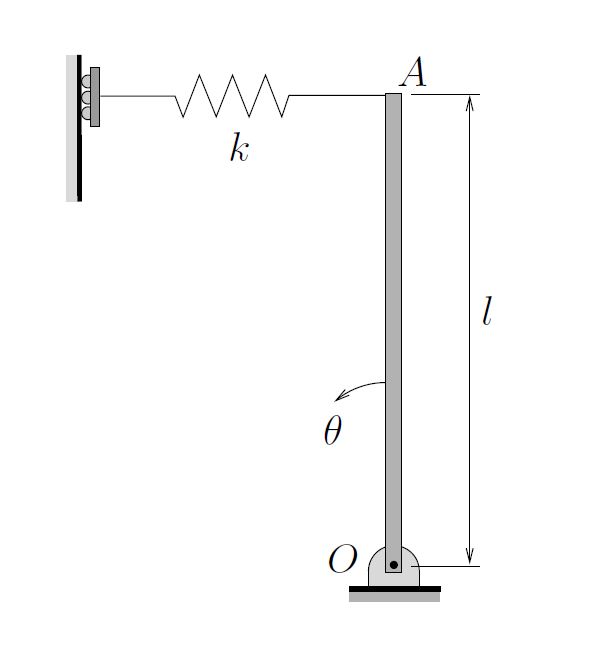

A thin uniform bar of length ![]() and mass

and mass ![]() is pinned at its lower end

is pinned at its lower end ![]() and supported by a linear spring at its upper end

and supported by a linear spring at its upper end ![]() . The spring remains horizontal and is unstretched when the bar is in the vertical position. Determine the equation of motion and natural frequency for small vibrations of the bar. Use the coordinate

. The spring remains horizontal and is unstretched when the bar is in the vertical position. Determine the equation of motion and natural frequency for small vibrations of the bar. Use the coordinate ![]() as indicated.

as indicated.