Approximate Methods for Multiple Degree of Freedom Systems: Rayleigh’s Quotient

For a conservative MDOF system, the total mechanical energy ![]() is a constant so that

is a constant so that

![]()

or using the representations in (9.1) and (9.2)

(9.3) ![]()

Now consider the system vibrating in one of its normal modes at a natural frequency ![]() . The amplitudes of the coordinates are given by

. The amplitudes of the coordinates are given by

![]()

where ![]() is the corresponding mode shape and

is the corresponding mode shape and ![]() is a constant. The derivatives of the coordinates will therefore be

is a constant. The derivatives of the coordinates will therefore be

![]()

The coordinates will have maximum values given by

(9.4) ![]()

which all occur simultaneously (when ![]() ). At the same instant,

). At the same instant, ![]() so the derivatives of the coordinates will all be zero (

so the derivatives of the coordinates will all be zero (![]() ).

).

Similarly the coordinate derivatives will have maximum values given by

(9.5) ![]()

when ![]() . At this instant,

. At this instant, ![]() so the coordinates themselves are all zero (i.e. the system is passing through its equilibrium configuration).

so the coordinates themselves are all zero (i.e. the system is passing through its equilibrium configuration).

In summary

![]()

Now, consider equation (9.3) at the instant when ![]() . We see that

. We see that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2} \bigl\{\!\dot{q}\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\!\bigl[m\bigr] \! \bigl\{\!\dot{q}\!\bigr\} +\frac{1}{2} \bigl\{\!q\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\!_{\text{MAX}}\!\bigl[k\bigr] \! \bigl\{\!q\!\bigr\}_{\text{MAX}} &= E \nonumber \\\frac{1}{2} \Bigl(A \!\bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\Bigr) \!\!\bigl[k\bigr] \! \Bigl(\! A \bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\} \!\Bigr) &= E\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0c1883c57e414c3b78d588ca92b1e5b1_l3.png)

or

(9.6) ![]()

Similarly, when ![]() we find

we find

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2} \bigl\{\!\dot{q}\!\bigr\}_{\text{MAX}}\!\bigl[m\bigr]\! \bigl\{\!\dot{q}\!\bigr\}_{\text{MAX}} +\frac{1}{2} \bigl\{\!q\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\!\bigl[k\bigr] \! \bigl\{\!q\!\bigr\} &= E \\\frac{1}{2} \Bigl( \! A p \bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\Bigr) \!\!\bigl[m\bigr] \! \Bigl(\! A p \bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\} \!\Bigr) &= E\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-00730dcc6e2ea07779a42f7e696b4044_l3.png)

or

(9.7) ![]()

Since the total energy ![]() is a constant for this conservative system, comparing equations (9.6) and (9.7 ) leads to the conclusion that

is a constant for this conservative system, comparing equations (9.6) and (9.7 ) leads to the conclusion that

![]()

or

(9.8) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \boxed{p^2 = \frac{\hspace{-1cm}\bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\!\bigl[k\bigr] \! \bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\} \rule{-3mm}{0pt}}{\bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\}\!\rule[4mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{T} \!\!\bigl[m\bigr] \! \bigl\{\!\Phi\!\bigr\} \rule{5mm}{0pt}}}\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bc5d3fda54d04bb096f88151aca21024_l3.png)

Equation (9.8) is known as Rayleigh’s Quotient. This result tells us that if a mode shape corresponding to a particular natural frequency is used in the ratio in (9.8), then the result will be the associated natural frequency squared.

By itself this is not a particularly useful result since typically, knowing ![]() and

and ![]() for a particular system, we must find

for a particular system, we must find ![]() as part of the process of determining the mode shapes in the first place. However, equation (9.8) can be useful for obtaining approximate natural frequencies for MDOF systems. In essence, what we do is estimate a mode shape

as part of the process of determining the mode shapes in the first place. However, equation (9.8) can be useful for obtaining approximate natural frequencies for MDOF systems. In essence, what we do is estimate a mode shape ![]() for the system and Rayleigh’s Quotient returns an associated estimate of the natural frequency. Obviously, the choice of

for the system and Rayleigh’s Quotient returns an associated estimate of the natural frequency. Obviously, the choice of ![]() will influence the value of the returned natural frequency, however it can be shown that if

will influence the value of the returned natural frequency, however it can be shown that if ![]() are the

are the ![]() natural frequencies on an

natural frequencies on an ![]() degree of freedom system, then for any assumed mode shape

degree of freedom system, then for any assumed mode shape ![]() the frequency

the frequency ![]() returned by Rayleigh’s Quotient satisfies

returned by Rayleigh’s Quotient satisfies

![]()

i.e. the frequency returned by Rayleigh’s Quotient will always be higher than the lowest natural frequency and lower than the highest natural frequency in the system. Typically we are more concerned with the lowest (fundamental) frequency in a system, for which Rayleigh’s Quotient establishes an upper bound. (This frequency also provides a lower bound on the highest natural frequency of a system but this is usually of less interest.)

Remarkably good estimates of the fundamental natural frequency can be obtained even if the assumed mode shape ![]() (also called a trial vector) is not equal to the actual first mode shape.

(also called a trial vector) is not equal to the actual first mode shape.

EXAMPLE

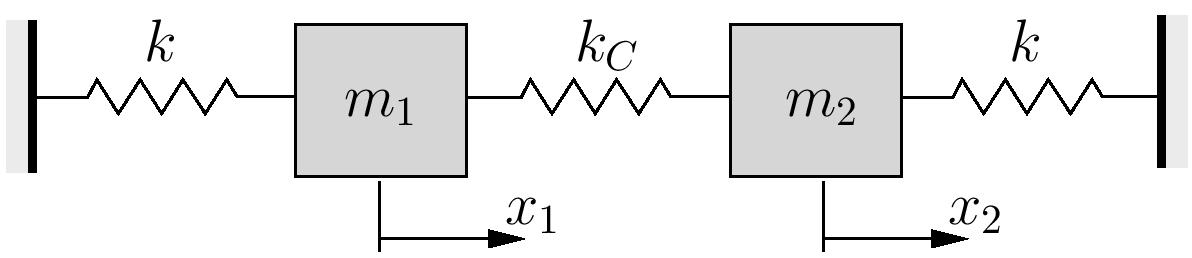

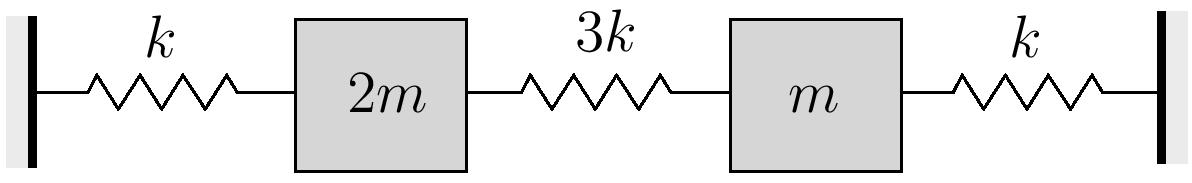

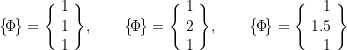

(a) For the system shown above, estimate the fundamental natural frequency using Rayleigh’s Quotient. Assume ![]() and use trial vectors of

and use trial vectors of

![]()

and comment on the results. It was previously determined that

![]()

![]()

(b) Repeat the calculations in part (a) assuming ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Note that the exact solution in this case is

![]()

![]()

EXAMPLE

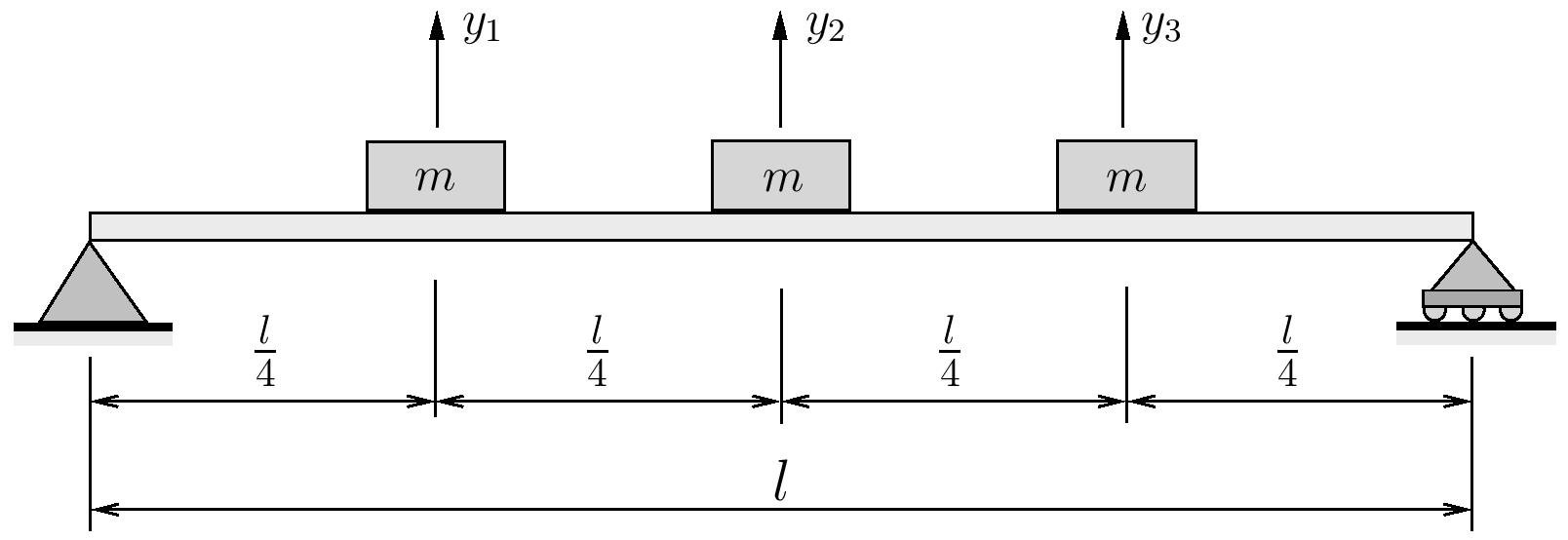

Use Rayleigh’s method to estimate the fundamental natural frequency for a light simply supported beam supporting three equally spaced identical masses.

Assume trial vectors of

Note that for this problem

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\bigl[ k \bigr] &=\frac{192 EI}{7 l^3}\Biggl[\begin{array}{rrr}23 & -22 & 9\\-22 & 32 & -22\\9 & -22 & 23\\\end{array}\vspace{4mm}\Biggr] \\\bigl[ m \bigr] &=m\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}1 & 0 & 0\\0 & 1 & 0\\0 & 0 & 1\\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e0b3cf362fb65699d432aedc2502b00d_l3.png)