Approximate Methods for Multiple Degree of Freedom Systems: Dunkerley’s Formula

Dunkerley’s Formula is another method of estimating the lowest (fundamental) natural frequency of a system without having to solve an eigenvalue problem. Rather than using the stiffness matrix, Dunkerley’s Method makes use of the flexibility matrix ![]() which is the inverse of the stiffness matrix.

which is the inverse of the stiffness matrix.

Starting with the equations of motion for a general ![]() degree of freedom system

degree of freedom system

![]()

and assuming simple simultaneous harmonic motion of the form

![]()

results in

(9.9) ![]()

Premultiplication of (9.9) by ![]() results in

results in

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}-\ensuremath{p}^2 \underbrace{\bigl[k\bigr]\!\!\rule[5mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{-1}}_{\bigl[a\bigr]}\bigl[m\bigr]\!\bigl\{\!\mathbb{A}\!\bigr\} + \underbrace{\bigl[k\bigr]\!\!\rule[5mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{-1}\bigl[k\bigr]}_{\bigl[1\bigr]}\!\bigl\{\!\mathbb{A}\!\bigr\} = \bigl\{0\bigr\}\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f423d427f05adaa6bdde3ba9a01beb2c_l3.png)

so that

![]()

or

![]()

As we have seen previously, for a non-trivial solution to exist it is required that

(9.10) ![]()

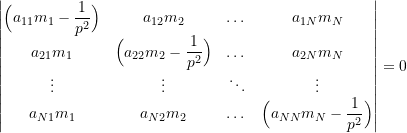

For simplicity we will assume that the mass matrix is diagonal. In that case, the determinant in (9.10) has the form

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\left| \left[\begin{matrix}a_{{1}{1}} & a_{{1}{2}} & \dots & a_{{1}{N}} \\a_{{2}{1}} & a_{{2}{2}} & \dots & a_{{2}{N}} \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\a_{{N}{1}} & a_{{N}{2}} & \dots & a_{{N}{N}} \\\end{matrix}\right]\left[\begin{matrix}m_1 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & m_2 & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & m_N \\\end{matrix}\right]-\left[\begin{matrix}\dfrac{1}{p^2} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & \dfrac{1}{p^2} & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & \dfrac{1}{p^2} \\\end{matrix}\right] \right|= 0\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8b3c9e184e7b53caf902fdec93d6dbf1_l3.png)

or

(9.11)

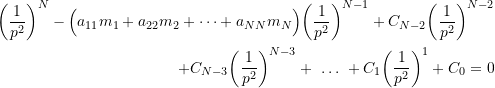

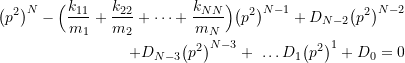

Expanding (9.11) produces the characteristic equation which has the form

(9.12)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are constants (which will depend on

are constants (which will depend on ![]() and

and ![]() ) which we do not need to consider here.

) which we do not need to consider here.

Let the ![]() roots of (9.12) be given by

roots of (9.12) be given by

![]()

Since these ![]() values are the roots, the characteristic equation could also be written in the form

values are the roots, the characteristic equation could also be written in the form

(9.13) ![]()

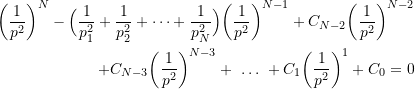

which is a completely equivalent polynomial to (9.12). Expanding (9.13) we get

(9.14)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the same constants which appeared in (9.12). Comparing the

are the same constants which appeared in (9.12). Comparing the ![]() terms in equations (9.12) and (9.14) shows that

terms in equations (9.12) and (9.14) shows that

(9.15) ![]()

To this point no approximations have been made. Now however, we note that for many systems the higher natural frequencies are significantly larger than the fundamental natural frequency ![]() so that

so that

![]()

As a result, ignoring all but the first term on the LHS of (9.15) results in

![]()

or

![]()

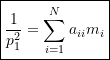

or more generally

(9.16)

Equation (9.16) is known as Dunkerley’s Formula and provides an estimate of the fundamental natural frequency of a system. Due to the terms that have been neglected, the natural frequency obtained using Equation (9.16) will be lower than the actual fundamental natural frequency. Dunkerley’s Formula therefore provides a lower bound on the lowest natural frequency of the system (in contrast to Rayleigh’s Quotient which provided an upper bound on the lowest natural frequency).

Note that as long as the mass matrix is diagonal, Equation (9.16)

![]()

can be written as

![]()

where ![]() is defined as the natural frequency of the single degree of freedom system that results when mass

is defined as the natural frequency of the single degree of freedom system that results when mass ![]() is the only mass in the system (i.e. all other masses in the system are assumed to be zero). This is because of the fact that if

is the only mass in the system (i.e. all other masses in the system are assumed to be zero). This is because of the fact that if ![]() is the only mass in the system then

is the only mass in the system then ![]() represents the deflection of the mass (in the positive i

represents the deflection of the mass (in the positive i![]() coordinate direction) when a unit load is applied to the mass

coordinate direction) when a unit load is applied to the mass ![]() (again in the positive i

(again in the positive i![]() coordinate direction). The effective stiffness of the (single degree of freedom) system is then

coordinate direction). The effective stiffness of the (single degree of freedom) system is then

![]()

so that

![]()

as defined above. This interpretation can be useful in applying Dunkerley’s Formula in some instances.

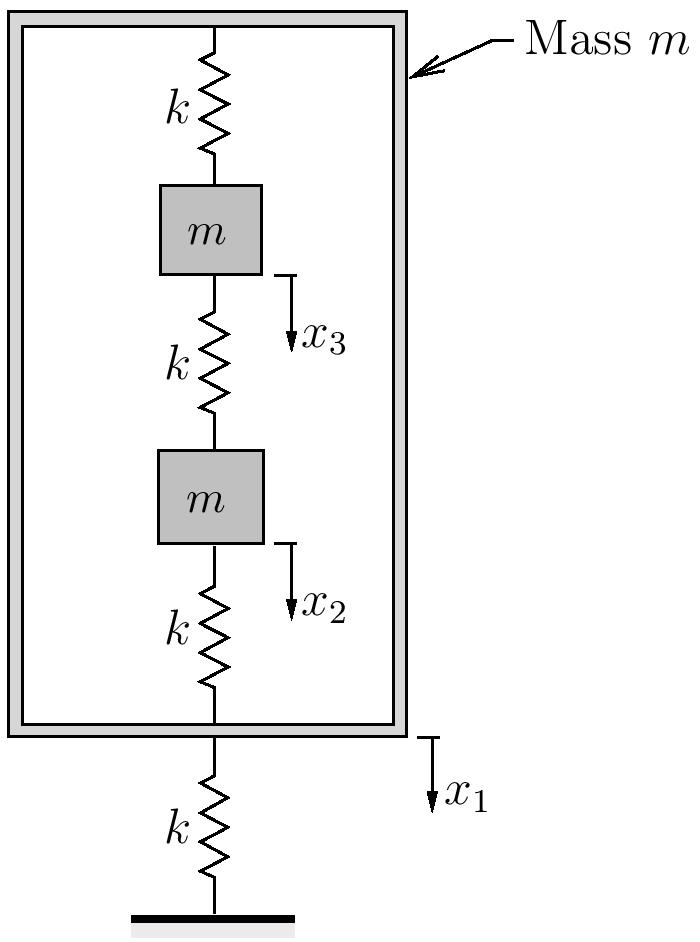

EXAMPLE

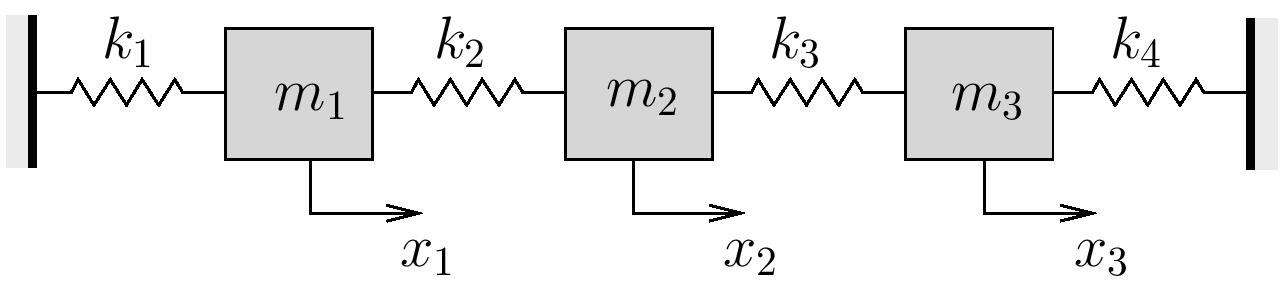

Estimate the fundamental natural frequency for the system shown below using Dunkerley’s Method.

Consider the following cases:

i)

![]()

ii)

![]()

iii)

![]()

Note that the stiffness matrix for this problem is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\bigl[ k \bigr] =\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}k_1 + k_2 & -k_2 & 0 \\-k_2 & k_2 + k_3 & -k_3 \\0 & -k_3 & k_3 + k_4 \\\end{array}\Biggr]\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-273ee7a3ebd1314bec77497d4d9d116f_l3.png)

so that ![]() is (Note: show full screen view)

is (Note: show full screen view)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\bigl[ a \bigr] =\frac{1}{k_1 (k_2 k_3 + k_2 k_4 + k_3 k_4) + k_2 k_3 k_4}\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}k_2 k_3 + k_2 k_4 + k_3 k_4 & k_2\bigl( k_3 + k_4 \bigr) & k_2 k_3 \\k_2\bigl( k_3 + k_4 \bigr) & \bigl( k_1 + k_2 \bigr)\bigl( k_3 + k_4 \bigr) & \bigl( k_1 + k_2 \bigr)k_3 \\k_2 k_3 & \bigl( k_1 + k_2 \bigr)k_3 & k_1 k_2 + k_1 k_3 + k_2 k_3 \\\end{array}\Biggr]\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3adeb5d89acac11020ac93204792ffda_l3.png)

EXAMPLE

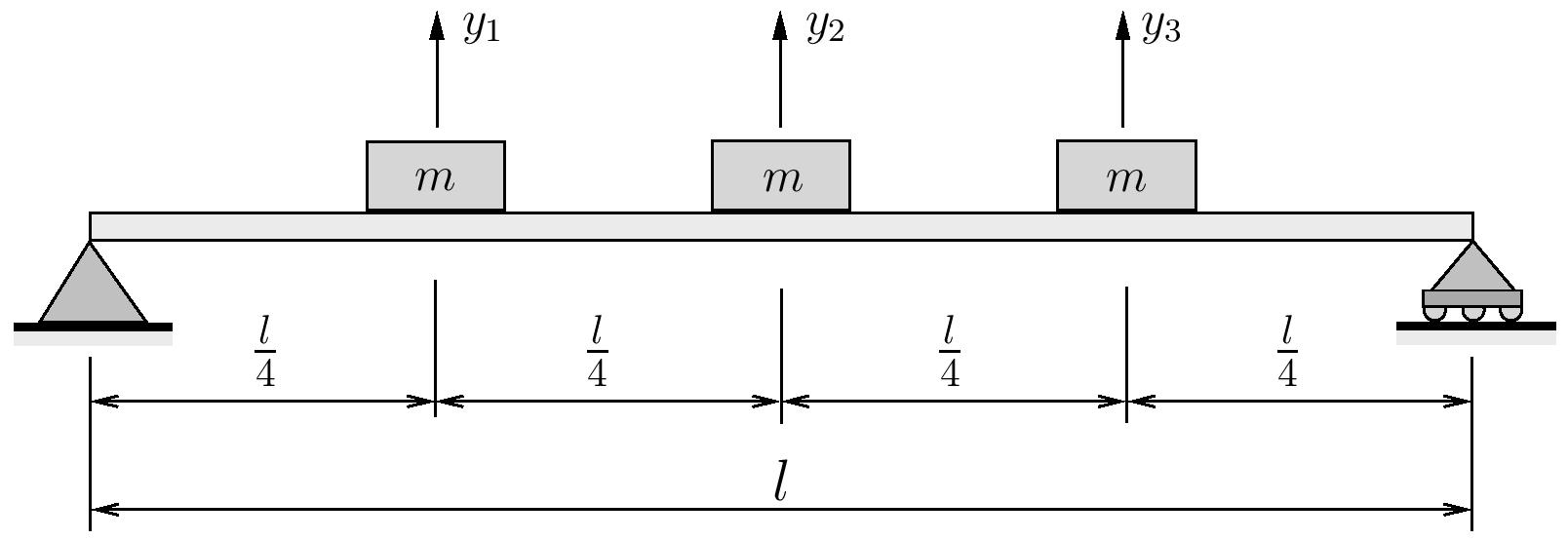

Use Dunkerley’s method to estimate the fundamental natural frequency for a light simply supported beam supporting three equally spaced identical masses.

Note that for this system

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\bigl[ a \bigr] =&\frac{l^3}{768 EI}\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}9 & 11 & 7\\11 & 16 & 11\\7 & 11 & 9\\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\bigl[ k \bigr] =&\frac{192 EI}{7 l^3}\Biggl[\begin{array}{rrr}23 & -22 & 9\\-22 & 32 & -22\\9 & -22 & 23\\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\bigl[ m \bigr] =&m\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}1 & 0 & 0\\0 & 1 & 0\\0 & 0 & 1\\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2d7b0dca2259bd0e7f15c8e14c292594_l3.png)

Dunkerley’s Formula to Estimate The Highest Natural Frequency

The ideas behind Dunkerley’s Formula, with a slightly different formulation, can also be used to estimate the highest natural frequency in a system. To see this start with (9.9)

![]()

Premultiplication by ![]() produces

produces

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}-\ensuremath{p}^2 \underbrace{\bigl[m\bigr]\!\!\rule[5mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{-1}\bigl[m\bigr]}_{\bigl[1\bigr]}\!\bigl\{\!\mathbb{A}\!\bigr\} + \bigl[m\bigr]\!\!\rule[5mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{-1}\bigl[k\bigr]\!\bigl\{\!\mathbb{A}\!\bigr\} = \bigl\{0\bigr\}\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-89496022c63a6804e360bbce2856d43f_l3.png)

or

![]()

This again requires, for non-trivial solutions,

(9.17) ![]()

If we again assume that the mass matrix is diagonal, then the inverse is simply

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\left[\begin{matrix}m_1 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & m_2 & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & m_N \\\end{matrix}\right]\!\!\!\rule[15mm]{0pt}{0pt}^{-1}=\left[\begin{matrix}\frac{1}{m_1} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & \frac{1}{m_2} & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & \frac{1}{m_N} \\\end{matrix}\right]\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-137842700abadeacc7f03d4f841aa6db_l3.png)

As a result, the determinant in (9.17) has the form

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\left| \left[\begin{matrix}\frac{1}{m_1} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & \frac{1}{m_2} & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & \frac{1}{m_N} \\\end{matrix}\right]\left[\begin{matrix}k_{{1}{1}} & k_{{1}{2}} & \dots & k_{{1}{N}} \\k_{{2}{1}} & k_{{2}{2}} & \dots & k_{{2}{N}} \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\k_{{N}{1}} & k_{{N}{2}} & \dots & k_{{N}{N}} \\\end{matrix}\right]-\left[\begin{matrix}\ensuremath{p}^2 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\0 & \ensuremath{p}^2 & \dots & 0 \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\0 & 0 & \dots & \ensuremath{p}^2 \\\end{matrix}\right] \right|= 0\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6c068af66a52ff1108e06701675b9f6e_l3.png)

or

(9.18) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \left|\begin{matrix}\Bigl(\dfrac{k_{{1}{1}}}{m_1} - p^2 \Bigr) & \dfrac{k_{{1}{2}}}{m_1} & \dots& \dfrac{k_{{1}{N}}}{m_1} \\[5mm]\dfrac{k_{{2}{1}}}{m_2} & \Bigl(\dfrac{k_{{2}{2}}}{m_2} - p^2\Bigr) & \dots &\dfrac{k_{{2}{N}}}{m_2} \\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\\dfrac{k_{{N}{1}}}{m_N} & \dfrac{k_{{N}{2}}}{m_N} & \dots& \Bigl(\dfrac{k_{{N}{N}}}{m_N} - p^2\Bigr) \\\end{matrix}\right|= 0\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f7c8d95b63c8c8ec1da543206bb7e1c7_l3.png)

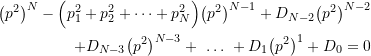

Expanding (9.18) produces a characteristic equation with the form

(9.19)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are again constants which depend on

are again constants which depend on ![]() and

and ![]() . The

. The ![]() roots of (9.19) correspond to the natural frequencies of the system given by

roots of (9.19) correspond to the natural frequencies of the system given by

![]()

Once again, since these ![]() values are the roots of the characteristic equation, we could equivalently write the characteristic equation as

values are the roots of the characteristic equation, we could equivalently write the characteristic equation as

(9.20) ![]()

which expanded gives

(9.21)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the same constants as in (9.19) Comparing the

are the same constants as in (9.19) Comparing the ![]() terms in equations (9.19) and (9.21) shows that

terms in equations (9.19) and (9.21) shows that

(9.22) ![]()

Since ![]() is the largest natural frequency in the system, we ignore all of the other terms on the LHS of (9.22) to get

is the largest natural frequency in the system, we ignore all of the other terms on the LHS of (9.22) to get

![]()

or more generally

(9.23)

Due to the terms that have been ignored in (9.22), the frequency obtained using (9.23) will be larger than the highest natural frequency in the system. As a result, this version of Dunkerley’s Formula provides an upper bound on the largest natural frequency of the system.

EXAMPLE

For the system shown below:

(a) Use Rayleigh’s quotient to find an upper bound to the lowest natural frequency. Use a trial vector of

(b) Use Dunkerley’s method to find a lower bound for the lowest natural frequency.

(c) Use Dunkerley’s method to find an upper bound for the highest natural frequency.

Note that for this problem,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\bigl[ k \bigr] =&k\Biggl[\begin{array}{rrr}3 & -1 & -1 \\-1 & 2 & -1 \\-1 & -1 & 2 \\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\bigl[ a \bigr] =&\frac{1}{3k}\Biggl[\begin{array}{rrr}3 & 3 & 3 \\3 & 5 & 4 \\3 & 4 & 5 \\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\bigl[ m \bigr] =&m\Biggl[\begin{array}{ccc}1 & 0 & 0\\0 & 1 & 0\\0 & 0 & 1\\\end{array}\Biggr] \\\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-fab7604daffd835fda6d38cbefc6ad30_l3.png)