Vibrations of Continuous Systems: Lateral Vibrations of Beams

Equation of Motion

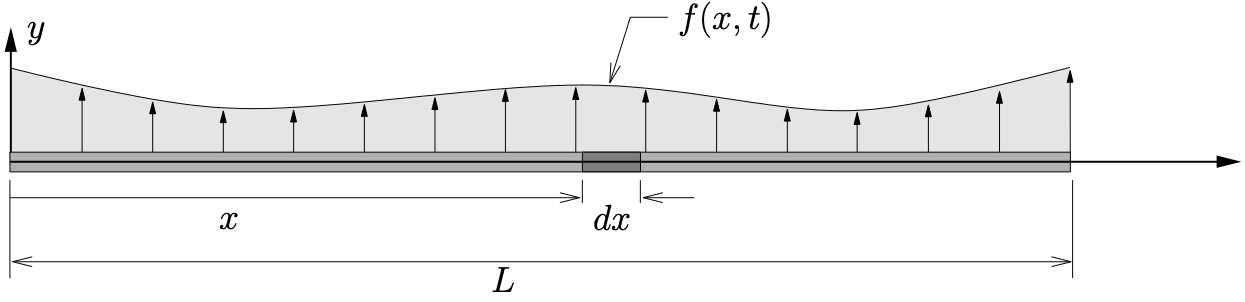

Figure 10.6: Uniform beam undergoing lateral vibrations

Consider a beam, shown in Figure 10.6(a) which has a length ![]() , density

, density ![]() (mass per unit volume) and Young’s modulus

(mass per unit volume) and Young’s modulus ![]() which is acted upon by a distributed load

which is acted upon by a distributed load ![]() (per unit length) acting laterally along the beam. Let

(per unit length) acting laterally along the beam. Let ![]() measure the lateral deflection of the beam and assume that only small deformations occur. Figure 10.6(b) shows the FBD/MAD for an infinitesimal element of the beam with mass

measure the lateral deflection of the beam and assume that only small deformations occur. Figure 10.6(b) shows the FBD/MAD for an infinitesimal element of the beam with mass ![]() . By applying Newton’s Law’s and considering moments about the left end of the element we find

. By applying Newton’s Law’s and considering moments about the left end of the element we find

![]()

![]()

As a first order approximation we can write that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}M(x+dx) &= M(x) + \frac{\partial M}{\partial x} dx \\[2mm]V(x+dx) &= V(x) + \frac{\partial V}{\partial x} dx \\\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9d0d6fc0da5d8b3dd08deca92716c163_l3.png)

so that the above becomes

![]()

![]()

![]()

or

(10.23) ![]()

which is a well known result from beam theory. In the vertical direction we then have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}+\!\!\uparrow\sum F = ma:\qquadV(x) - V(x+dx) + f(x,t) dx &= \rho A dx \ensuremath{\frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2}} \\{V(x)} - \Bigl[{V(x)} + \frac{\partial V}{\partial x} dx\Bigr]+ f(x,t) dx &= \rho A dx \ensuremath{\frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2}} \\-\frac{\partial V}{\partial x} {dx} + f(x,t) {dx} &= \rho A {dx} \ensuremath{\frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2}} \\\intertext{or}-\frac{\partial V}{\partial x} + f(x,t) &= \rho A \ensuremath{\frac{\partial^2 y}{\partial t^2}} \\\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ae188845c571c83e0aa957d679b4f2b0_l3.png)

Note: For small motions, the shear forces act vertically to a first order approximation. The actual vertical components would be for example ![]() where

where ![]() can be obtained from the slope of the beam. However, for small motions,

can be obtained from the slope of the beam. However, for small motions, ![]() , so

, so ![]() is used here as the vertical component. A similar remark holds for the

is used here as the vertical component. A similar remark holds for the ![]() term.

term.

Now, using 10.23 we can write that

![]()

so the equation of motion becomes

(10.24) ![]()

For small deformations the bending moment in the beam is related to the deflection by

![]()

so that 10.24 becomes

![]()

or

(10.25) ![]()

This is the general equation which governs the lateral vibrations of beams. If we limit ourselves to only consider free vibrations of uniform beams (![]() ,

, ![]() is constant), the equation of motion reduces to

is constant), the equation of motion reduces to

![]()

which can be written

(10.26) ![]()

where

(10.27)

Note that this is not the wave equation.

Solution To Equation of Motion

Once again we look for solutions which represent a mode shape undergoing \sshm of the form

![]()

This results in

![]()

so 10.26 becomes

![]()

Separating the ![]() and

and ![]() terms we find

terms we find

![]()

Again, since the LHS depends only on ![]() and the RHS depends only on

and the RHS depends only on ![]() and they must be equal for all values of

and they must be equal for all values of ![]() and

and ![]() , both sides must be equal to a constant, which we call

, both sides must be equal to a constant, which we call ![]() , so that

, so that

![]()

This results in equations

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}\frac{\ensuremath{c}^2}{\ensuremath{\mathbb{Y}}(x)} \frac{d^4 \ensuremath{\mathbb{Y}}}{d x^4} &= p^2 \\[2mm]-\frac{1}{\ensuremath{\mathbb{T}}(t)} \frac{d^2 \ensuremath{\mathbb{T}}}{d t^2} &= p^2\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b5ffb3864f9ed63b3bbe1ec6dde1df53_l3.png)

or

(10.28a) ![]()

(10.28b) ![]()

where

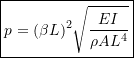

(10.29) ![]()

Note for future reference that

![]()

so that

(10.30)

The solution to 10.28b is as we have seen

![]()

To find the solution to 10.28a, which is a 4![]() order linear ODE with constant coefficients, we assume a solution of the form

order linear ODE with constant coefficients, we assume a solution of the form

![]()

The equation of motion then becomes

![]()

or

![]()

The four roots to this equation are

![]()

The total solution will be a linear combination of solutions, one for each of the above roots,

(10.31) ![]()

where each of the ![]() may be complex. However, by using Euler’s identity

may be complex. However, by using Euler’s identity

![]()

and introducing the hyperbolic ![]() and

and ![]() functions

functions

![]()

10.31 can be written

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\begin{split}\ensuremath{\mathbb{Y}}(x) =\ &G_1 \Bigl[ \cosh{\beta x} + \sinh{\beta x} \Bigr] +G_2 \Bigl[ \cosh{\beta x} - \sinh{\beta x} \Bigr] \\ +&G_3 \Bigl[ \cos{\beta x} + i \sin{\beta x} \Bigr] +G_4 \Bigl[ \cos{\beta x} - i \sin{\beta x} \Bigr]\end{split}\end{equation*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d5b3db9b29706690dcf2d63a2327895e_l3.png)

or

(10.32) ![]()

where

![]()

The advantage of expressing the solution as in 10.32 is that all of the terms involved are real. We see that ![]() and

and ![]() are complex conjugates, while

are complex conjugates, while ![]() and

and ![]() are real.

are real.

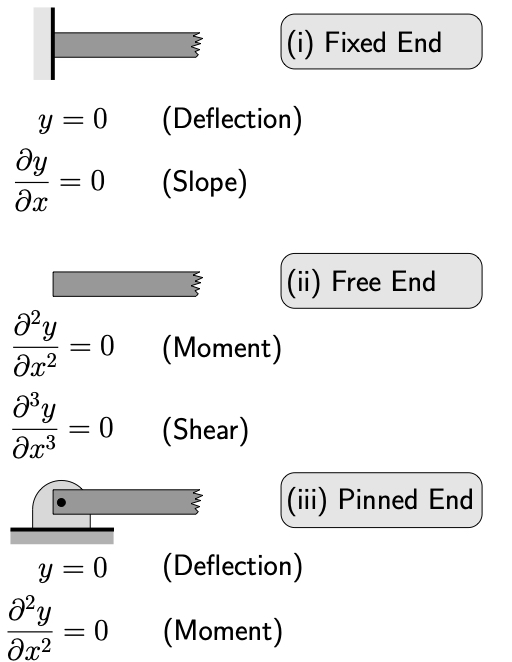

As can be seen there are four constants to be determined which requires that four boundary conditions be specified. These will often be determined with one pair of boundary conditions specified at each end, depending on the type of support. Figure 10.7 shows three of the most common support conditions and the pairs of boundary conditions that are associated with each type of support.

EXAMPLE

A uniform beam (density ![]() , cross–sectional area

, cross–sectional area ![]() , flexural rigidity

, flexural rigidity ![]() ) of length

) of length ![]() is fixed at one end and free at the other.

is fixed at one end and free at the other.

Determine expressions for the natural frequencies and associated mode shapes for this beam.

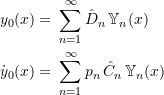

Complete Response of Lateral Motion of Beam

We have again found an infinite number of solutions which satisfy the equation of motion 10.26 given by

(10.33) ![]()

where ![]() is the

is the ![]() natural frequency and

natural frequency and ![]() is the associated mode shape, both of which depend on the specific boundary conditions present. The general solution will then be a superposition of all of the solutions in 10.33,

is the associated mode shape, both of which depend on the specific boundary conditions present. The general solution will then be a superposition of all of the solutions in 10.33,

(10.34) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*}y(x,t) =& \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} y_n(x,t) \nonumber \\y(x,t) =& \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\ensuremath{\mathbb{Y}}_n(x) \biggl[ \hat{C}_n \, \sin{p_n t} + \hat{D}_n \, cos{p_n t} \biggr]\end{align*}](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d88f5f4ce3a2bc6d2b155969aa36e372_l3.png)

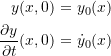

The constants ![]() and

and ![]() are to be determined from the initial conditions of the beam. If the initial displacement and velocity of the beam are specified as

are to be determined from the initial conditions of the beam. If the initial displacement and velocity of the beam are specified as

then 10.34 gives

![]() and

and ![]() can then be found from

can then be found from

(10.35) ![]()

(10.36) ![]()

where once again the orthogonality property of the mode shape has been used

![]()

This is once again beyond the scope of this course.