Forces and Moments: Moments

Introducing a New Notation

Henceforth, we will use a new notation for simplicity. Recall that when a vector ![]() is represented in CVN as

is represented in CVN as ![]() , the capital letters

, the capital letters![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() represent scalar components. Their values can be negative or positive, depending on the directions of the components relative to

represent scalar components. Their values can be negative or positive, depending on the directions of the components relative to ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . For simplicity and brevity in notations and formulations we introduce a magnitude-based notation and a scalar formulation starting in this section.

. For simplicity and brevity in notations and formulations we introduce a magnitude-based notation and a scalar formulation starting in this section.

In the magnitude-based notation, the capital letters, such as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , represent the magnitudes of the vectors, i.e.

, represent the magnitudes of the vectors, i.e. ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . This means they are positive.

. This means they are positive.

Note that capital letters or bold letters are used to label the vectors. They are just for naming purposes. The direction is always indicated by the arrows.

When using the magnitude-based notation, the direction of a vector (specifically a vector component) referred to by a non-bold capital letter within the text is denoted by little arrows if needed. The following example clarifies this convention.

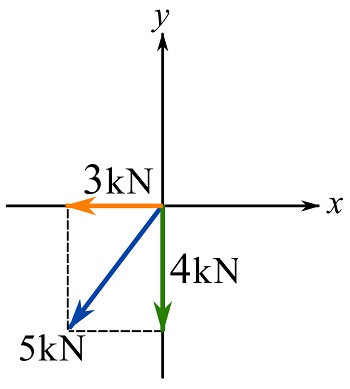

EXAMPLE

Consider the vector ![]() and its vector components

and its vector components ![]() and

and ![]() shown below.

shown below.

We can write,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split}F_x &= 3 \text { kN}\leftarrow\\F_y &= 4 \text { kN}\rightarrow\\F &= 5 \text { kN}\swarrow\end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-468d3cb15ef4b32f4f7da52ad5394afb_l3.png)

In the scalar formulation, the signs ![]() or

or ![]() in front of the (positive) variables, such as

in front of the (positive) variables, such as ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , indicate the direction of the vectors with respect to predefined Cartesian axes x, y, and z.

, indicate the direction of the vectors with respect to predefined Cartesian axes x, y, and z.

For instance, in the case of coplanar forces ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() in a Cartesian coordinate system, the resultant force

in a Cartesian coordinate system, the resultant force ![]() is,

is,

![]()

Decomposing the sum along the x and y axes as,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split}\bold R_x &= \sum_i^n \bold F_{xi}\\\bold R_y &= \sum_i^n \bold F_{yi}\\\end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1babd96b01d4ae489b1c3449838aa453_l3.png)

we can use the scalar formulation to write,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split}R_x &= \overset{+}{\rightarrow}\sum F_{ix}\\R_y &= +\uparrow\sum F_{iy}\end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cc84bb75486f1d71575cb5c07dddffc7_l3.png)

where the non-bold capital letters are magnitudes and the arrows (![]() ,

, ![]() ) specify the positive directions of the Cartesian axes. If any of the vector components

) specify the positive directions of the Cartesian axes. If any of the vector components ![]() and

and ![]() points in the negative direction of its corresponding axes, then a minus sign “

points in the negative direction of its corresponding axes, then a minus sign “![]() ” is added in front of its magnitude. This use of notation is clarified by an example as follows.

” is added in front of its magnitude. This use of notation is clarified by an example as follows.

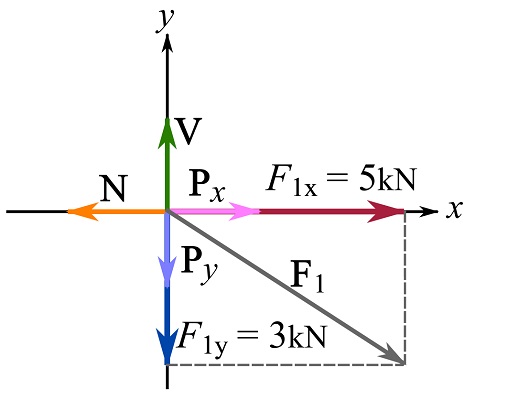

EXAMPLE

Considering the coplanar forces shown in the figure, formulate the resultant force in its Cartesian components.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split}\bold R_x = \sum \bold F_x \implies R_x &=\overset{+}{\rightarrow}\sum F_x= -N+P_x + 5 \text{ kN}\\\bold R_y = \sum \bold F_y \implies R_y &= +\uparrow\sum F_y = V - P_y - 3\text{ kN}\end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0156cb4a1d5ddb64faf1831ecde045ba_l3.png)

The minus sign in front of the magnitude of any of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() is because the vector is in the negative direction of its corresponding Cartesian axis.

is because the vector is in the negative direction of its corresponding Cartesian axis.

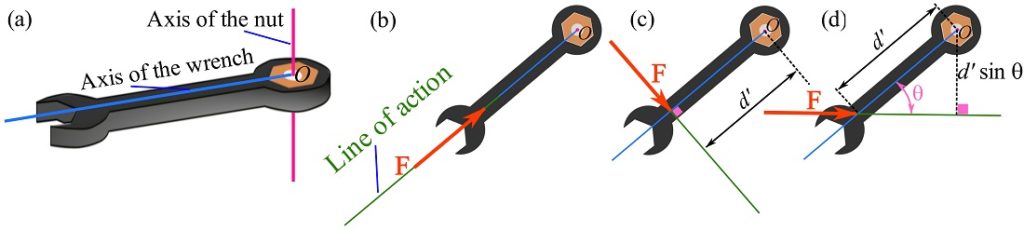

Moment by a force

When a body is subjected to a force, the force may rotate or produce a tendency of rotation for the body. For a tangible example, consider a wrench applied to a nut or head of a bolt as shown in Fig. 3.8a. If we apply a force by pulling or pushing along the handle of the wrench, the wrench will not turn (Fig. 3.8b). However, the wrench and the nut will rotate or pivot about the vertical axis passing through the center of the nut (point ![]() ) if we exert a force on either side of the handle (Fig. 3.8c). This tendency, created by a force, to rotate, twist, or pivot a body, is called a torque or the moment caused by a force; or simply the moment.

) if we exert a force on either side of the handle (Fig. 3.8c). This tendency, created by a force, to rotate, twist, or pivot a body, is called a torque or the moment caused by a force; or simply the moment.

We should pay attention to the term tendency. In the wrench example, we are able to keep turning and fastening the nut to a certain degree beyond which we are not able to turn the wrench anymore (due to muscle weakness for instance). However, we are still able to push or pull the wrench and generate a tendency of rotation on the nut.

We can experiment to find that the extent of rotation of the wrench depends on how hard we exert the force on the handle. Also, we can change the position of our hand on the handle of the wrench; the further our hand is away from the nut, it gets easier (less force is needed) for turning or fastening the nut. Moreover, we can understand that changing the angle of the force applied on the handle makes it easier or harder to rotate the wrench or the nut; the easiest effort comes when our hand is perpendicular to the handle (Fig. 3.8c and d). These observations indicate that the magnitude of the moment (tendency of rotation) depends on the angle between the line of action of the force and the handle, the magnitude of the force, and the distance between the pivoting point and the point at which the force is applied.

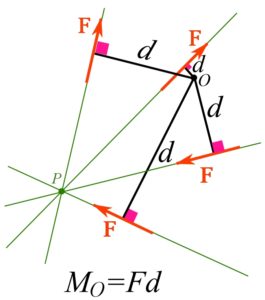

The magnitude of a moment of a force about a point (pivot point), ![]() , caused by a force,

, caused by a force, ![]() can be calculated with the following scalar formula.

can be calculated with the following scalar formula.

(3.12) ![]()

where ![]() is the magnitude of the force (absolute value) and

is the magnitude of the force (absolute value) and ![]() is the perpendicular distance (absolute value) from the pivot point to the line of action of the force as demonstrated in Fig 3.9.

is the perpendicular distance (absolute value) from the pivot point to the line of action of the force as demonstrated in Fig 3.9.

Equation 3.12 indicates that the magnitude of a moment only depends on the magnitude of the force, ![]() , and the perpendicular distance from the pivot point,

, and the perpendicular distance from the pivot point, ![]() to the line of action of the force. This perpendicular line segment is called the moment arm. By Eq. 3.12, the dimension and unit of the moment are

to the line of action of the force. This perpendicular line segment is called the moment arm. By Eq. 3.12, the dimension and unit of the moment are ![]() and

and ![]() respectively.

respectively.

In the example of a wrench, Fig. 3.8, the magnitude of the moment is ![]() .

.

Remark: the line of action of a force, and the moment arm are coplanar.

Remark: the moment of a force about a point on the line of action of the force is zero (because ![]() ). It is intuitive as well.

). It is intuitive as well.

Remark: a moment is not a rotation, but, it causes rotation or a tendency to rotate.

The following interactive tool illustrates how the moment of a force (blue vector) about the point ![]() is calculated. The force is acting at the point

is calculated. The force is acting at the point ![]() .

.

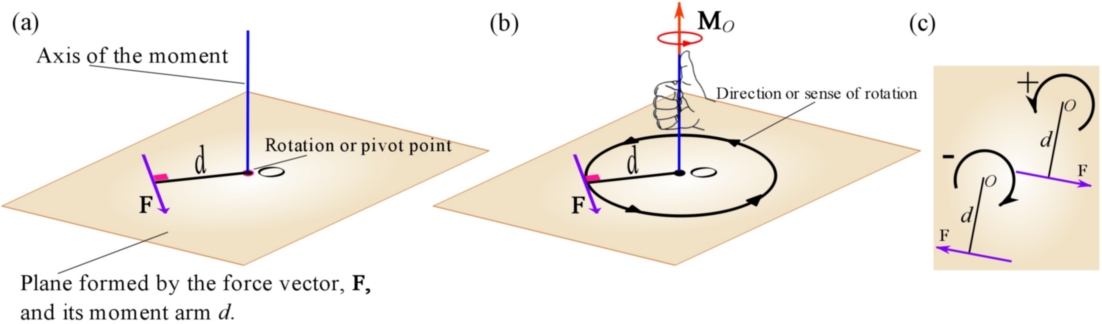

Direction of a moment

Since the rotation tendency has a direction and the tendency is caused by a moment, , a moment has a sense of direction. The direction of a moment is defined and expressed by its moment axis and the right-hand rule. The axis of a moment is a line passing through the pivot point and perpendicular to the plane that contains the force vector (line of action of the force) and its moment arm (Fig. 3.10a). The right-hand rule is then utilized to establish the direction of the moment. By this rule, when fingers curl in the rotation direction, the thumb indicates the sense of an arrow defining the moment direction on the moment axis (3.10b).

Having both a magnitude and a direction, a moment is in fact a vector quantity. For two-dimensional (or coplanar) problems, where all forces (and pivot points) lie in a plane (say x-y plane), all moment vectors are perpendicular to the plane (and along the z axis). To make a moment vector easily seen, it is shown by a curled arrow. By convention, a counterclockwise rotation is associated with a positive moment, and a clockwise rotation with a negative moment (3.10c). This sign convention is not mandatory and either direction can be set as the positive direction. However, it is important that the positive direction selected is consistent through solving a problem.

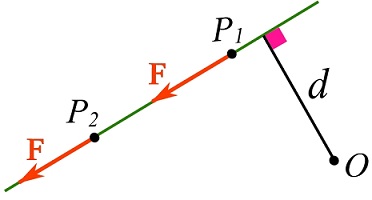

Principle of Transmissibility

The location of the point at which the force is acting does not affect its moment about a given point as long as the point is selected on the line of action of the force (Fig 3.11). This fact is referred to as the principle of transmissibility stating that sliding a force along its line of action does not change its moment about a given point. By this principle, a force vector is designated as a sliding vector. The proof of this principle using vector calculation is presented in the next subsection.

Remark: the moment of a force about a point does not depend on the point (on the body) at which the force is acting as long as the force slides (changes position) along its line of action.

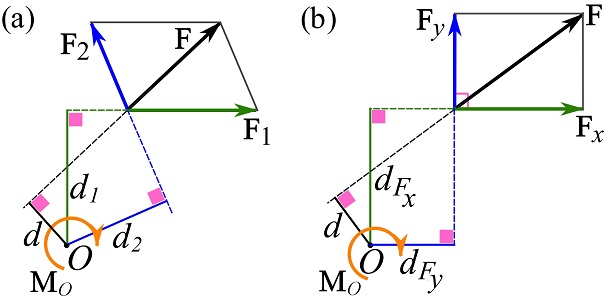

Principle of moments (Varignon’s Theorem)

The principle of moments or Varignon’s theorem (Pierre Varignon (1654–1722) states that the moment of a force about a point equals the sum of the moments of the components of the force about the point. For a two-dimensional example, a force ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are coplanar components of

are coplanar components of ![]() as shown in Fig 3.12a. Then, the principle of moments declares that,

as shown in Fig 3.12a. Then, the principle of moments declares that,

![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are the magnitudes of

are the magnitudes of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() ; and

; and ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are the moments arms of

are the moments arms of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Note that the counterclockwise rotation is associated with positive moments (Fig 3.10c), therefore the moment of

respectively. Note that the counterclockwise rotation is associated with positive moments (Fig 3.10c), therefore the moment of ![]() and

and ![]() about

about ![]() are negative and the moment of

are negative and the moment of ![]() about

about ![]() is positive.

is positive.

Calculating the moment of a force about a point usually becomes simpler when using the Cartesian components of the force and with principle of moments. For example, the following equation holds for the force ![]() and its Cartesian components shown in Fig. 3.12b.

and its Cartesian components shown in Fig. 3.12b.

![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are the magnitudes of

are the magnitudes of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively.

respectively.

Remark: for calculating the moment of a forces about a point in two-dimensions, the magnitudes of the rectangular components of the force are used. In other words, the absolute values of the scalar components are involved.

The following interactive tool illustrates the principle of moments for calculating the moment of a force about a point in two-dimensions. Change the direction of the force and observe how its moment about the point is calculated based on the moments of the force components.

The vector form of the principle of the moments is presented in the next section.

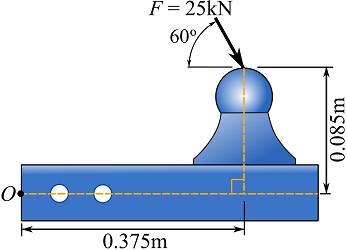

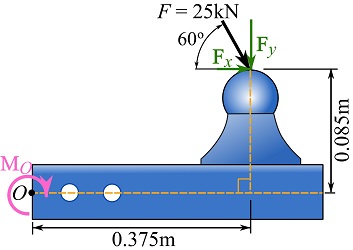

EXAMPLE 3.2.1

Determine the moment of the force, acting on the trailer ball mount, about point ![]() shown in the figure. Use the principle of the moments.

shown in the figure. Use the principle of the moments.

SOLUTION

Determine the rectangular components of the force (see figure below).

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split}\bold F&= \bold F_x + \bold F_y\\F_x &= 25\cos 60^\circ =12.5\text{ kN}\rightarrow \\F_y &= 25\sin 60^\circ = 21.7\text{ kN} \downarrow\end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c815f47d04e3f2924922602c732cbc01_l3.png)

Determine the moment of each of the force components about point ![]() and scalar-add the together. The counterclockwise rotation is associated with positive moments.

and scalar-add the together. The counterclockwise rotation is associated with positive moments.

![]()

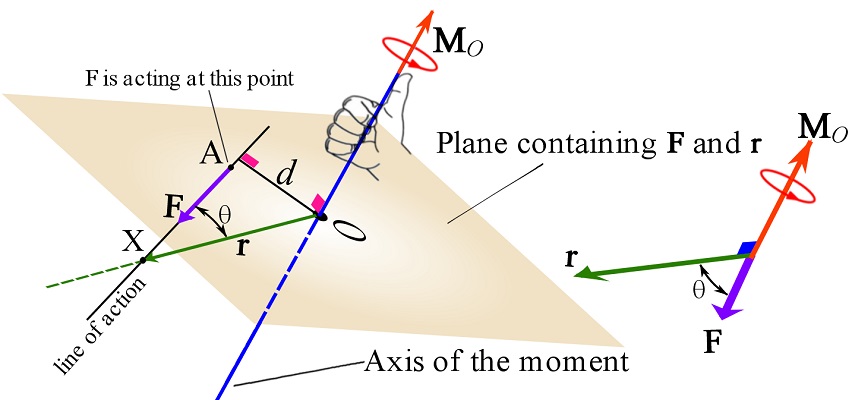

Cross product for moment calculation

The formulation of moment magnitude, ![]() , is called the scalar formulation. Although this formulation gives the moment magnitude, it does not provide the direction of the moment. To express a moment in its vector form, including both magnitude and direction, the vector cross product (Section 2.8) is recruited. The moment (vector) of a force

, is called the scalar formulation. Although this formulation gives the moment magnitude, it does not provide the direction of the moment. To express a moment in its vector form, including both magnitude and direction, the vector cross product (Section 2.8) is recruited. The moment (vector) of a force ![]() about point

about point ![]() is,

is,

(3.13) ![]()

where ![]() is a position vector directed from the pivot point O to any point (X) on the line of action of the force vector

is a position vector directed from the pivot point O to any point (X) on the line of action of the force vector ![]() (Fig 3.13). The vector

(Fig 3.13). The vector ![]() is not necessarily the moment arm, but it can be called the quasi-moment arm vector or moment arm vector. This formulation of the moment of a force is referred to as the vector formulation. he nature of the cross product provides both magnitude and direction for a moment. The magnitude of a moment is the magnitude of its cross product formulation,

is not necessarily the moment arm, but it can be called the quasi-moment arm vector or moment arm vector. This formulation of the moment of a force is referred to as the vector formulation. he nature of the cross product provides both magnitude and direction for a moment. The magnitude of a moment is the magnitude of its cross product formulation,

(3.14) ![]()

which agrees with Eq. 3.12.

The direction of ![]() , indicated by the cross product, is perpendicular to both

, indicated by the cross product, is perpendicular to both ![]() and

and ![]() . In other words,

. In other words, ![]() is perpendicular to the plane containing

is perpendicular to the plane containing ![]() and

and ![]() (it is equivalent to say that the plane contains

(it is equivalent to say that the plane contains ![]() and the line of action of the force). The vector formulation of a moment is demonstrated in Fig 3.13.

and the line of action of the force). The vector formulation of a moment is demonstrated in Fig 3.13.

Remark: the order of the operation resulting in ![]() matters; by the properties of the cross product

matters; by the properties of the cross product ![]() . Only

. Only ![]() will give a direction that complies with the direction indicated by the right-hand rule mentioned earlier.

will give a direction that complies with the direction indicated by the right-hand rule mentioned earlier.

The CVN facilitates calculating moments expressed by the vector formulation. With ![]() and

and ![]() expressed in CVN, the moment of

expressed in CVN, the moment of ![]() about a point

about a point ![]() becomes,

becomes,

(3.15) ![]()

which can be evaluated through the symbolic use of the determinant (see Section 2.8) as,

(3.16) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\bold M_O=\bold r \times \bold F=\left\|\begin{matrix}\bold i & \bold j & \bold k \\r_x & r_y & r_z \\F_x & F_y & F_z \\\end{matrix}\right\|\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-757e11a8010e6a5df39cdff0e9038268_l3.png)

where the determinant evaluated as (see Section 2.8),

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\left\|\begin{matrix} \bold i & \bold j & \bold k \\ r_x & r_y & r_z \\ F_x & F_y & F_z \end{matrix}\right\|=\left\|\begin{matrix} r_y & r_z \\ F_y & F_z \end{matrix}\right\|\bold i - \left\|\begin{matrix} r_x & r_z \\ F_x & F_z \end{matrix}\right\|\bold j + \left\|\begin{matrix} r_x & r_y \\ F_x & F_y \end{matrix}\right\|\bold k\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9b2c1b58029dff5d3048215fca933b3b_l3.png)

The following interactive example demonstrates the vector formulation of the moment of a force about a point in three dimensions.

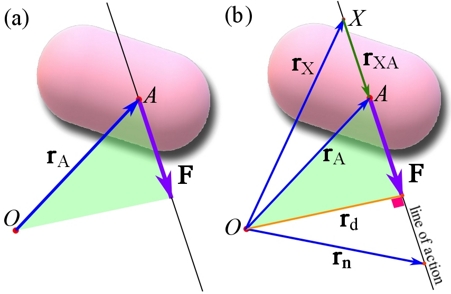

Proof of the Principle of Transmissibility (Vector Form)

Suppose a body and a force ![]() acting at a point

acting at a point ![]() of the body (Fig. 3.14a). Consider a point

of the body (Fig. 3.14a). Consider a point ![]() anywhere in the space (may also be a point of the body) but not on the line of action of

anywhere in the space (may also be a point of the body) but not on the line of action of ![]() . If the moment arm vector

. If the moment arm vector ![]() is considered, the moment of

is considered, the moment of ![]() about

about ![]() is

is ![]() . Similarly, the moment of

. Similarly, the moment of ![]() about point

about point ![]() is

is ![]() if any other point

if any other point ![]() on the line of action is chosen to construct a moment arm vector as

on the line of action is chosen to construct a moment arm vector as ![]() . Our purpose is now to prove

. Our purpose is now to prove ![]() . The key to this proof is noting that there exist a position (displacement) vector

. The key to this proof is noting that there exist a position (displacement) vector ![]() on the line of action such that

on the line of action such that ![]() (Fig. 3.14b). Thereby,

(Fig. 3.14b). Thereby,

![]()

proves the principle. The proof uses the distributivity of the cross product. The term ![]() is zero because the vectors are collinear, or the angle between them is zero. Since the above proof holds for any two moment arm vectors (Figure 3.14b shows some possibilities), the moment is independent of the location of

is zero because the vectors are collinear, or the angle between them is zero. Since the above proof holds for any two moment arm vectors (Figure 3.14b shows some possibilities), the moment is independent of the location of ![]() being on the line of action.

being on the line of action.

The Principle of moments (Varignon’s Theorem) for a vector in CVN

Let ![]() be a force with

be a force with ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() as its Cartesian components. Then, the following equation holds for the moment of

as its Cartesian components. Then, the following equation holds for the moment of ![]() and its components about a point

and its components about a point ![]() .

.

(3.17) ![]()

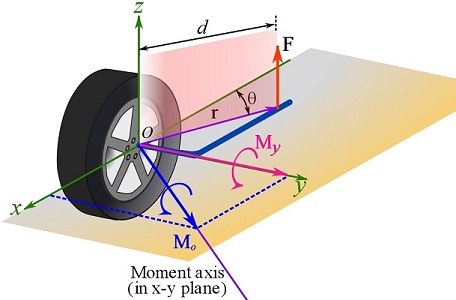

In the previous subsection, the moment of a force about a point has been discussed. A key concept regarding a moment is that a moment is created about a point and has an axis passing through the point. Physically, the tendency of rotation created at the point by the moment is about an axis perpendicular to the plane of the force and the point(Fig. 3.10 and 3.13). In reality, an object may be only allowed to rotate around a specific axis, which could be not perpendicular to the plane. On the other hand, a moment is a vector quantity and consequently it can have components along different axes as well. Therefore, a quantity can be found as the moment about an axis.

For example, applying a vertical force on the handle of an L-shape wrench to loosen a lug nut of a car tire creates a moment (![]() ) at the nut (

) at the nut (![]() ) with the axis of the moment as shown in Fig. 3.15. The axis of the moment is neither along the handle nor along the extension bar of the wrench. If we are interested to find the moment (as a component of

) with the axis of the moment as shown in Fig. 3.15. The axis of the moment is neither along the handle nor along the extension bar of the wrench. If we are interested to find the moment (as a component of ![]() ) that rotates the nut, we should find the moment (

) that rotates the nut, we should find the moment (![]() ) whose axis is along the wrench extension bar being the y axis in the figure.

) whose axis is along the wrench extension bar being the y axis in the figure.

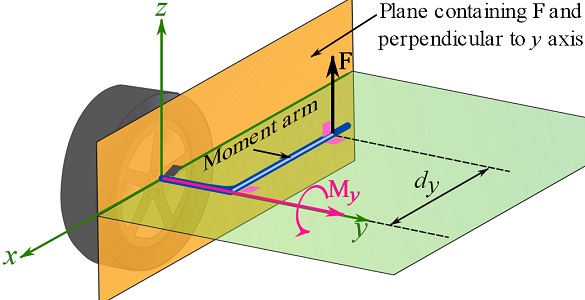

In the particular case shown in Fig. 3.16, where (the line of action of) ![]() is in a plane perpendicular to the specified axis of interest (the y axis), the magnitude of the moment of

is in a plane perpendicular to the specified axis of interest (the y axis), the magnitude of the moment of ![]() about the y axis is

about the y axis is ![]() where

where ![]() is the moment arm of

is the moment arm of ![]() in the plane perpendicular to the moment axis (Fig. 3.16).

in the plane perpendicular to the moment axis (Fig. 3.16).

In two dimensional problems where all forces are coplanar in a plane, say ![]() plane (e.g. Fig 3.10), any moment about any point in the plane is in fact a moment about the z axis (or an axis parallel to the z axis).

plane (e.g. Fig 3.10), any moment about any point in the plane is in fact a moment about the z axis (or an axis parallel to the z axis).

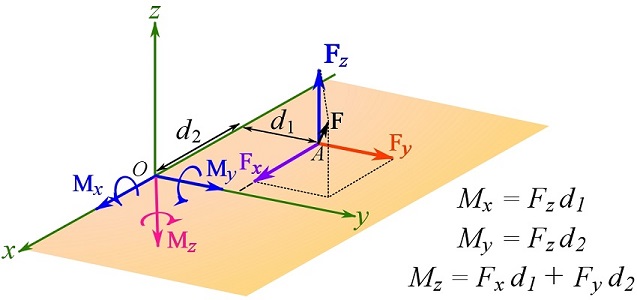

Another case is obtaining the moments of a force (at some point ![]() of the space) about the three Cartesian axes. This problem simplifies if the application of the force is slid to the x-y plane (or the x-z or y-z plane) and then resolve the force into its rectangular components. An example is shown in Fig. 3.17. A force

of the space) about the three Cartesian axes. This problem simplifies if the application of the force is slid to the x-y plane (or the x-z or y-z plane) and then resolve the force into its rectangular components. An example is shown in Fig. 3.17. A force ![]() is at point

is at point ![]() in the x-y plane (or in some plane parallel to x-y plane). Each component creates some moment(s) about some Cartesian axis (or axes) as shown in the figure.

in the x-y plane (or in some plane parallel to x-y plane). Each component creates some moment(s) about some Cartesian axis (or axes) as shown in the figure.

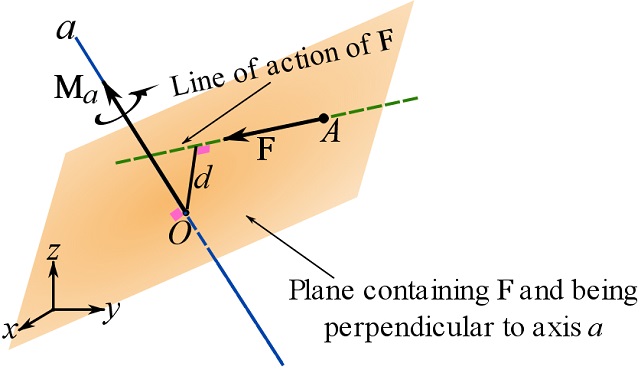

In general, determining the magnitude of the moment of a force about an specified axis needs finding a plane containing the line of action of the force and perpendicular to the axis of interest, and then finding the moment arm of the force in the plane (Fig 3.18). This approach is called the scalar formulations.

Calculations using the scalar formulation of the moment of a force about an axis is not always easy in three dimensions. Therefore, a vector formulation is used.

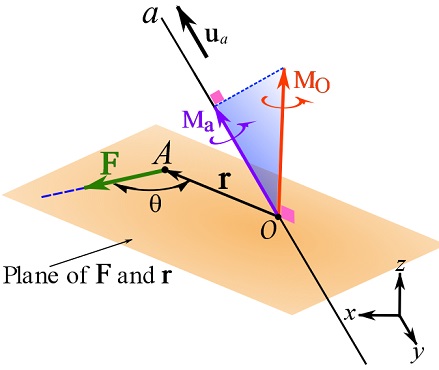

Let ![]() be a force and

be a force and ![]() an arbitrary point of a specified axis

an arbitrary point of a specified axis ![]() as demonstrated in Fig. 3.19. Then the moment of the force about

as demonstrated in Fig. 3.19. Then the moment of the force about ![]() is

is ![]() , where,

, where, ![]() is the quasi-moment arm vector constructed from

is the quasi-moment arm vector constructed from ![]() to any point of the line of action of the force (Fig. 3.19).

to any point of the line of action of the force (Fig. 3.19).

If ![]() is the unit vector of axis

is the unit vector of axis ![]() , then the component of

, then the component of ![]() along the specified axis is determined by the dot product,

along the specified axis is determined by the dot product,

(3.18) ![]()

The term ![]() is called the triple scalar product. The triple scalar product orthogonally projects the vector

is called the triple scalar product. The triple scalar product orthogonally projects the vector ![]() onto an axis with the direction defined by

onto an axis with the direction defined by ![]() . The quantity

. The quantity ![]() is a scalar; a positive value indicates that

is a scalar; a positive value indicates that ![]() is in the direction of

is in the direction of ![]() , whereas a negative value indicates that

, whereas a negative value indicates that ![]() is in the opposite direction of the axis. See Section 2.7 for more information.

is in the opposite direction of the axis. See Section 2.7 for more information.

If ![]() and

and ![]() are expressed using CVN, their scalar components can form a matrix as,

are expressed using CVN, their scalar components can form a matrix as,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{bmatrix}u_{a_x} & u_{a_y} & u_{a_z}\\r_x & r_y & r_z\\F_x & F_y & F_z\end{bmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-999535c794443cb3763eb2398d301605_l3.png)

and the triple scalar product can be computed by calculating the determinant of the matrix,

(3.19) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[M_a=\bold u_a\cdot(\bold r\times \bold F)= \left\|\begin{matrix}u_{a_x} & u_{a_y} & u_{a_z}\\r_x & r_y & r_z\\F_x & F_y & F_z\end{matrix}\right\|\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4cdac7fee8d605cb64c6f6d9ac9a7595_l3.png)

The proof is by expanding the equation ![]() and comparing it with the determinant result.

and comparing it with the determinant result.

Remark: for determining the moment of a force about a specified axis, both the location and the direction of the axis influence the results.

Remark: the physical meaning of the Cartesian components of a moment vector ![]() are moments about the three Cartesian axes.

are moments about the three Cartesian axes.

In the following interactive example, we intend to determine the moment of a force, applied at a corner of the pyramid, about either of the specified axes ![]() or

or ![]() . In the example,

. In the example, ![]() is the moment of

is the moment of ![]() about point

about point ![]() ,

, ![]() is the moment of

is the moment of ![]() about the axis

about the axis ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the moment of

is the moment of ![]() about the axis

about the axis ![]() .

.

Videos

Calculating Moments in 2D:

Calculating Moments in 3D (About a Point or Axes):