Engineering Mechanics: STATICS: Scalars and vectors

Basic definitions

Scalars and vectors are mathematical objects and they are useful for quantifying physical quantities.

Scalar. A scalar is a real number. For example ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on .

, and so on .

Scalar quantity. A scalar quantity is a quantity that can be described by a single real number. This number specifies the magnitude or size of that quantity. For example mass, speed, area, temperature, and pressure are scalar quantities.

Sometimes a scalar quantity is simply referred to as scalar. For example, “mass is a scalar” is equivalent to stating: “mass is a scalar quantity”.

Mathematical operations on scalars follow the usual rules of arithmetic.

Vector. A vector is a mathematical object that is understood by its size (magnitude) and its direction. This definition perfectly fulfils the requirements of engineering mechanics. However, for a more rigorous mathematical definition, please refer to section 14.2.8.

Vector quantity. A vector quantity is a quantity characterized by both a magnitude and a direction. For example velocity, force, acceleration, and moment are all vector quantities.

The magnitude (sometimes referred to as the norm) of a vector is always taken to be a positive number. For example the magnitude of the velocity of a moving object is the speed of that object. Speed is always measured and reported as a positive number.

The terms vector and vector quantity can be equivalently used.

In this book, we distinguish between a vector and a scalar using special notations. The notation for a vector is a bold upper-case letter ![]() or an upper-case letter with a symbolic overhead arrow

or an upper-case letter with a symbolic overhead arrow ![]() . By convention, the direction of the arrow is from left to right and it does not convey any information about the direction of the vector itself. The magnitude of a vector is denoted by a regular upper-case letter

. By convention, the direction of the arrow is from left to right and it does not convey any information about the direction of the vector itself. The magnitude of a vector is denoted by a regular upper-case letter ![]() or the vector notation embedded by two vertical lines

or the vector notation embedded by two vertical lines ![]() or

or ![]() . The embedding vertical line notation is also used to denote the absolute value of a scalar, for example

. The embedding vertical line notation is also used to denote the absolute value of a scalar, for example ![]() where

where ![]() is a real number. In some text the notation of vector magnitude is a double-vertical-line notation

is a real number. In some text the notation of vector magnitude is a double-vertical-line notation ![]() and the absolute value of a scalar is shown by

and the absolute value of a scalar is shown by ![]() . In this book,

. In this book, ![]() is used for both cases.

is used for both cases.

Using an upper-case letter with a symbolic overhead arrow is recommended when writing notes, assignments, or exams.

Graphical representation of vectors

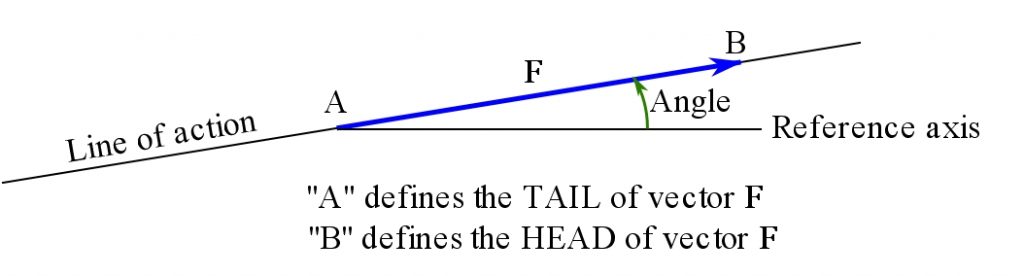

A graphical or geometrical representation of vectors is by directed line segments or arrows. Actually, a directed line segment is a vector itself.

A line segment is a finite-length piece of a straight line. It is defined by two ending points on a straight line.

A directed line segment (arrow) is a line segment with a defined direction. To define the direction, one of the segment’s end point is distinguished as the tail, and consequently the other one as head. Thereby, the r direction is defined as the sense of direction from the tail to the head of the segment. A directed line segment can be displayed by an arrow such that the arrow head defines the sense of direction. The line that is coincident with an arrow is called the line of action. The orientation or direction of an arrow (its tail is already known or defined) with respect to a fixed axis (a line) is defined by an angle formed between the axis and the line of action of the arrow. Figure 1 shows a directed line segment or arrow representing the vector ![]() with its defined terms.

with its defined terms.

Figure 1. Geometric representation of a directed line segment (arrow) or a vector.

A directed line segment or simply an arrow has both the direction and length. The length of an arrow is defined as its magnitude. An arrow has both a direction and a magnitude, therefore, an arrow is a vector. To be more precise an arrow is a geometric vector. In this book, vectors and arrow are equivalent.

Zero vector. The zero vector, denoted by ![]() or

or ![]() , is a vector of length zero. The zero vector does not point toward any direction, therefore, its direction is undefined.

, is a vector of length zero. The zero vector does not point toward any direction, therefore, its direction is undefined.

An important remark with a vector is that the position of a directed line segment or a vector in the space does not change the properties of the vector; because a vector is defined only by its direction and magnitude. As a result, two vectors are equal if they have the same direction and magnitude. Examples of equal vectors are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Equivalent vectors.

Vector operations using the parallelogram rule and trigonometry

The following are mathematical operations defined on vectors:

- Multiplication (or division) by a scalar.

- Vector addition (or subtraction).

- Vector products (dot product and cross product).

The first two operations are the fundamental operations. Vector products are special functions on vectors discussed in sections 14.2.6 and 14.27. In this section, the first two operations are discussed.

Multiplication (and division) of a vector by a scalar

A vector can be multiplied by a scalar and the result is another vector. A vector ![]() multiplied by a scalar

multiplied by a scalar ![]() will be equal the vector

will be equal the vector ![]() . This operation is denoted by

. This operation is denoted by ![]() . Division of a vector by a scalar

. Division of a vector by a scalar ![]() is the same as multiplication by

is the same as multiplication by ![]() . Multiplication of a vector by a scalar is implemented by this rule:

. Multiplication of a vector by a scalar is implemented by this rule:

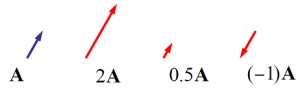

Scalar multiplication simply scales the magnitude (length) of a vector if the scalar is a positive number. The operation also reverses the direction of the vector if the scalar is a negative number.

The following figure demonstrates different vectors as the results of multiplication of ![]() by a scalar.

by a scalar.

Figure 3. Multiplication of a vector by a scalar.

Remark: multiplication of any vector, ![]() , by zero results in the zero vector:

, by zero results in the zero vector: ![]() .

.

Remark: multiplying a vector by a scalar scales its magnitude: if ![]() , then

, then ![]() in which

in which ![]() is the absolute value of the scalar

is the absolute value of the scalar ![]() .

.

Colinear vectors. Vectors on the same straight line are called colinear vectors. In other word, ![]() and

and ![]() are colinear if and only if there is an scalar

are colinear if and only if there is an scalar ![]() such that

such that ![]() . If

. If ![]() then the absolute value of

then the absolute value of ![]() is

is ![]() , because

, because ![]() . According to this definition, the zero vector is colinear with all other vectors.

. According to this definition, the zero vector is colinear with all other vectors.

It should be noted that parallel arrows or parallel vectors (vectors with parallel lines of action) are colinear because they can be moved on the same straight line.

Concurrent vectors. Vectors with their tails starting at the same point are called concurrent. This definition is only for the sake of graphical representation of arrows as vectors. Any number of vector can become concurrent once they are moved (re-drawn) such chat they all start from the same point.

Unit vector. A unit vector is a vector of magnitude ![]() . Any vector can be written as a scalar multiplication of a unit vector with the same direction:

. Any vector can be written as a scalar multiplication of a unit vector with the same direction: ![]() such that the notation

such that the notation ![]() indicates the unit vector (

indicates the unit vector (![]() ) in the direction of

) in the direction of ![]() . Any vector

. Any vector ![]() can become a unit vector if scaled by

can become a unit vector if scaled by ![]() . In this case we write

. In this case we write ![]() and call

and call ![]() the unit vector of

the unit vector of ![]() . Obviously,

. Obviously, ![]() is colinear with

is colinear with ![]() .

.

Normalizing a vector. Making a unit vector out of a vector is called normalizing a vector. The resultant unit vector only shows the direction of the original vector.

Vector addition

Vector addition is a vector operation that produces another vector. The addition of two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() resulting in a vector

resulting in a vector ![]() is denoted as:

is denoted as: ![]() . There are two equivalent rules (laws) for vector addition: triangle rule, and parallelogram law.

. There are two equivalent rules (laws) for vector addition: triangle rule, and parallelogram law.

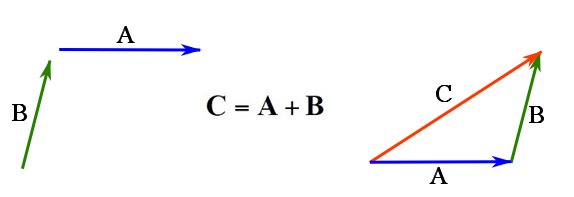

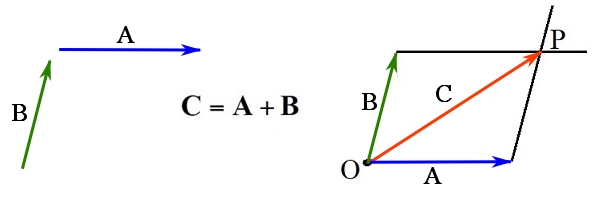

To calculate ![]() using the triangle rule follow these steps:

using the triangle rule follow these steps:

- Put

and

and  head to tail (or tail to head), and then,

head to tail (or tail to head), and then, - Close the triangle with the vector

.

.

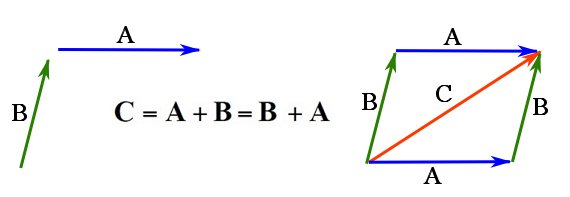

Figure 4 demonstrates the triangle rule for vector addition.

Figure 4. Addition of two vectors by The triangle rule.

Figure 5. Commutative property of vector addition.

- Bring the vectors to join at a point, say

, by their tails (make the vectors concurrent).

, by their tails (make the vectors concurrent). - From the head of each vector draw a line parallel to the other vector. These two lines intersect at a point

and form two adjacent lines of a parallelogram.

and form two adjacent lines of a parallelogram. - Draw a vector on the diagonal of the parallelogram from point

to the point

to the point  . This vector is the resultant vector

. This vector is the resultant vector  .

.

The figure below demonstrates vector addition using the parallelogram law.

Figure 6. The parallelogram law.

Figure 7. Vector subtraction.

Remark: while vector addition is commutative (![]() , vector subtraction is not commutative because

, vector subtraction is not commutative because ![]() . In fact,

. In fact, ![]() .

.

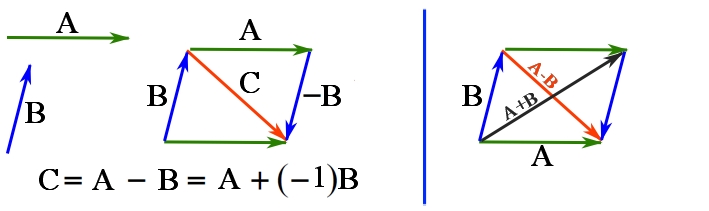

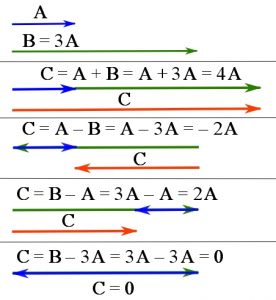

Addition of colinear vectors. The addition of colinear vectors are naturally handled by the triangle rule. Examples of vector addition in the case of colinear vectors are demonstrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Vector addition of parallel or colinear vectors.

Figure 9. Successive addition of 3 vectors using the triangle rule.

Trigonometry for vector operations

The triangle and parallelogram rules graphically give the resultant vector such that the direction of the vector can be understood. To calculate the magnitude of the resultant vector and the angle it makes with other vectors, trigonometry laws are used. Basic trigonometry laws are:

Figure 10. Basic trigonometry laws.

Figure 11. Sine and Cosine Laws.

Example 1

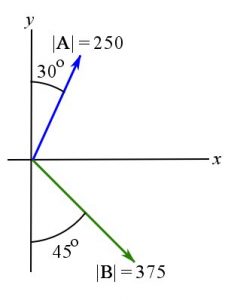

Determine the magnitude of the resultant vector ![]() and its direction measured counterclockwise from the positive x-axis shown.

and its direction measured counterclockwise from the positive x-axis shown.

Solution

— to be added —

Remark: It should be understood that the magnitude of vector addition is not necessarily equal the addition of the magnitudes. In other words, ![]() . In fact,

. In fact, ![]() always holds. This statement, called the triangle inequality, can be explored or proved by using the Cosine law.

always holds. This statement, called the triangle inequality, can be explored or proved by using the Cosine law.

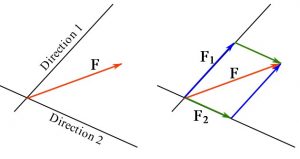

Vector components and Cartesian vector notation

The vector operation ![]() can be considered as decomposing the vector

can be considered as decomposing the vector ![]() into two vector components

into two vector components ![]() and

and ![]() . This implies that

. This implies that ![]() has two components along the directions or lines of action of

has two components along the directions or lines of action of ![]() and

and ![]() (Figure 12). Given a set of directions, a component of a vector along each directions can be found by decomposing the vectors. Vector decomposition of

(Figure 12). Given a set of directions, a component of a vector along each directions can be found by decomposing the vectors. Vector decomposition of ![]() can be regarded as the reverse of the vector addition, which means finding vectors with known directions (but unknown magnitude) such that their addition equals

can be regarded as the reverse of the vector addition, which means finding vectors with known directions (but unknown magnitude) such that their addition equals ![]() . Decomposing a vector can be performed using the trigonometry laws.

. Decomposing a vector can be performed using the trigonometry laws.

Figure 12. Decomposing a (planar) vector into two components along two directions or lines.

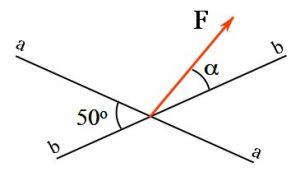

Example 2

The vector ![]() of magnitude

of magnitude ![]() is to be resolved into two components along the lines a-a and b-b. Determine the angle

is to be resolved into two components along the lines a-a and b-b. Determine the angle ![]() if the component of

if the component of ![]() along the line a-a has a magnitude of

along the line a-a has a magnitude of ![]() , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() .

.

Solution

— to be added —

Vector decomposition makes the resultant vector components on each direction collinear. This makes the addition of the vector components on a particular direction straight forward.

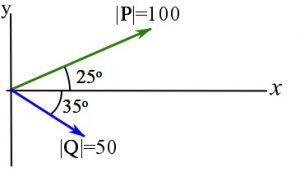

Example 3

Determine the resultant vector, ![]() , by decomposing the vectors

, by decomposing the vectors ![]() and

and ![]() on the two perpendicular lines (axes) denoted by

on the two perpendicular lines (axes) denoted by ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Solution

— to be added —

In the above example, the vectors are resolved into their components on the given axes and the collinear components of the vectors are added. Then, adding the resultant vectors on the axes gives the final resultant vector. This approach is a systematic approach for adding vectors.

Adding more than two vectors through a direct use of the parallelogram law, the Sine and Cosine laws is cumbersome. To do vector addition efficiently and in a systematic way, vectors are to be decomposed (resolved) onto a set of directions and the vector addition is performed using the colinear components.

In this regard, a set of directions simplifying the equations should be chosen. A convenient set of directions is a set of perpendicular directions called orthogonal axes. Orthogonal means perpendicular and an axis is a line to which a positive direction is associated by a vector colinear with the line. The positive direction of an axis sets a benchmark determining the positive (or negative) directions of the colinear vectors with the axis. For example, considering an axis ![]() shown in Figure 13, we say

shown in Figure 13, we say ![]() is in the positive direction and

is in the positive direction and ![]() is in the negative direction (with respect to the positive direction defined by the axis).

is in the negative direction (with respect to the positive direction defined by the axis).

Figure 13. Definition of an axis.

A vector decomposed (resolved) into its rectangular components can be expressed by using two possible notations namely the scalar notation (components) and the Cartesian vector notation. Both notations are explained for the planar conditions, and then expanded to three dimensions.

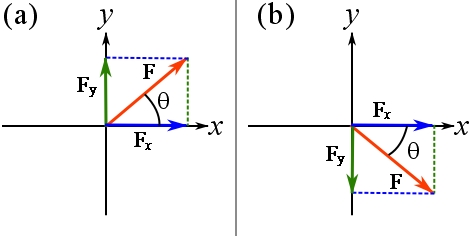

Rectangular vector components of coplanar vectors

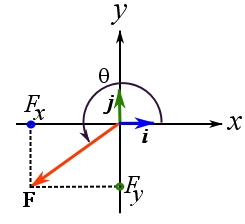

Consider a vector ![]() and its rectangular components resolved in a Cartesian system as shown in Figure 14. The

and its rectangular components resolved in a Cartesian system as shown in Figure 14. The ![]() and

and ![]() vector components of

vector components of ![]() are resolved and denoted by

are resolved and denoted by ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. The subscripts

respectively. The subscripts ![]() and

and ![]() denote the axes with which the components are colinear. The magnitude of the vector components are

denote the axes with which the components are colinear. The magnitude of the vector components are ![]() and

and ![]() . By the definition the magnitude of the vectors are (has to be) positive. Therefore, the magnitude of the components does not have information about their directions. To include the information about the directions of the vector components in a Cartesian system, scalar notation or scalar components are defined. Scalar components of a vector are signed magnitudes of its rectangular components. A scalar component is positive if the vector component is directed along the positive axis, and negative if the vector component is directed along the negative axis (opposite of the axis positive direction). For the vector components

. By the definition the magnitude of the vectors are (has to be) positive. Therefore, the magnitude of the components does not have information about their directions. To include the information about the directions of the vector components in a Cartesian system, scalar notation or scalar components are defined. Scalar components of a vector are signed magnitudes of its rectangular components. A scalar component is positive if the vector component is directed along the positive axis, and negative if the vector component is directed along the negative axis (opposite of the axis positive direction). For the vector components ![]() and

and ![]() shown in Figure 14, the scalar components are denoted by

shown in Figure 14, the scalar components are denoted by ![]() and

and ![]() . Note the regular and italic font face used for the notation. The scalar components of the vector shown in Figure 14a are

. Note the regular and italic font face used for the notation. The scalar components of the vector shown in Figure 14a are ![]() and

and ![]() both being positive. The scalar components of the vector shown in Figure 14b, however, are

both being positive. The scalar components of the vector shown in Figure 14b, however, are ![]() and

and ![]() . The scalar component

. The scalar component ![]() is negative, because its vector component

is negative, because its vector component ![]() is directed along the negative direction of the

is directed along the negative direction of the ![]() axis.

axis.

Figure 14. Components of vectors resolved in the Cartesian system.

By the definition (Figure 13), an axis has an associated vector showing the positive direction of the axis. Conventionally, the vector associated with an axis is considered to be a unit vector. Any vector on an axis (or parallel with the axis) is colinear with the unit vector of an axis. Therefore, any vector on an axis can be written as an scalar multiplier of the axis unit vector. The scalar multiplier is equal to the signed magnitude of the vector on the axis. It is positive if the vector is in the direction of the axis unit vector, and negative otherwise.

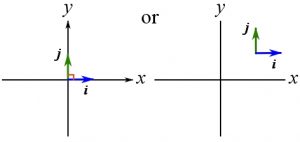

The unit vectors associated with the Cartesian ![]() and

and ![]() axes are denoted by bold small letters

axes are denoted by bold small letters ![]() and

and ![]() respectively and their respective small arrows are displayed on or near the Cartesian axes (Figure 15). Another possible notations are

respectively and their respective small arrows are displayed on or near the Cartesian axes (Figure 15). Another possible notations are ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Figure 15. The planar Cartesian axes and their unit vectors.

As a general rule any vector ![]() can be written as

can be written as ![]() in a Cartesian system. The notation

in a Cartesian system. The notation ![]() means any of the signs are independently possible. Showing a vector by the addition of its rectangular components expressed in terms of the unit vectors

means any of the signs are independently possible. Showing a vector by the addition of its rectangular components expressed in terms of the unit vectors ![]() and

and ![]() is called the Cartesian vector notation (CVN).

is called the Cartesian vector notation (CVN).

Remark: Both the scalar notation and the CVN are equivalent by noting that ![]() .

.

Remark: using the CVN is equivalent to resolving a vector in the Cartesian coordinate system.

Remark: components of a vector, referring to the vector components, are vectors, whereas, the scalar components, also known as the coordinates of a vector, are scalar.

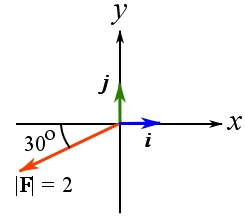

Example 4

Determine the rectangular components of ![]() (shown in the figure below) and write them in both the scalar notation and CVN.

(shown in the figure below) and write them in both the scalar notation and CVN.

Solution

— to be added —

Remark: the apparent location of a vector on a plane does not affect its component. You can always consider (draw) the Cartesian axes at the tail of a vector and calculate its components.

It is worthy to note the relationships among the scalar components, the magnitude, and the direction of a vector. Consider a Cartesian coordinate system in which angles are measured counter clockwise from the ![]() axis as demonstrated in Figure 16. Then the following equations hold:

axis as demonstrated in Figure 16. Then the following equations hold:

(1) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split}F^2&=\vert \bold F\vert^2 =F_x^2 + F_y^2 \quad \text{or}\quad F=\vert \bold F\vert =\sqrt {F_x^2 + F_y^2}\\ \tan \theta &= \frac{F_y}{F_x},\quad \sin\theta=\frac{F_y}{F},\quad\cos\theta=\frac{F_x}{F}\quad\text{for }0^\circ\le \theta < 360^\circ \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e652ce915f3b813eccd8b905397b44eb_l3.png)

Figure 16. The relationship between the scalar components of a vector and its magnitude, and direction.

Figure 17. Specifying the direction of a planar vector in the Cartesian frame by the acute angle that the vector makes with any of the Cartesian axes.

(2) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} F^2&=\vert \bold F\vert^2 =F_x^2 + F_y^2 \quad \text{or}\quad F=\vert \bold F\vert =\sqrt {F_x^2 + F_y^2} \\ \tan \theta &= \frac{\mid F_y\mid}{\mid F_x\mid},\quad \sin\theta=\frac{\mid F_y\mid}{F},\quad\cos\theta=\frac{\mid F_x\mid}{F}\quad\text{for }0^\circ\le \theta < 90^\circ \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-65a327b9271d775c7fa33aac812d0046_l3.png)

Remark: be cautious about the way the direction of a vector is specified and the proper formulation you should use for the calculations. If an acute angle is used, you should determine the signs of the scalar components by observing the direction of the vector components.

Remark: using an acute angle to specify the direction of an vector has a calculation advantage that ![]() is in the domain of the inverse trigonometric functions

is in the domain of the inverse trigonometric functions ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Planar vector operations using CVN (two dimensions)

Addition of several vectors ![]() using the CVN takes the following steps:

using the CVN takes the following steps:

1- Express each vector in CVN by resolving the vector to its rectangular components:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \bold F_1&=F_{1x}\bold i + F_{1y}\bold j\\ \bold F_2&=F_{2x}\bold i + F_{2y}\bold j\\ &\vdots\\ \bold F_n&=F_{nx}\bold i + F_{ny}\bold j \end{split} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-470598cce4a165eeb676af59cd7a7fee_l3.png)

2- Add the respective components (components on the same axis):

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \bold R_x&= (F_{1x}+F_{2x} + \dots + F_{nx})\bold i =(\sum_i^nF_{ix})\bold i= R_x\bold i\\ \bold R_y&= (F_{1y}+F_{2y} + \dots + F_{ny})\bold j = (\sum_i^nF_{iy})\bold j=R_y\bold j \end{split} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b090d29a068da928ad2ebf9a153b636e_l3.png)

in which ![]() and

and ![]() are the components of the resultant vector

are the components of the resultant vector ![]() .

.

3- Form the resultant vector ![]() . The magnitude and direction of

. The magnitude and direction of ![]() can be obtained by Eq. 1 or 2.

can be obtained by Eq. 1 or 2.

The above steps can be summarized as:

(3) ![]()

in which ![]() and

and ![]() represent the algebraic sums of the scalar components along the

represent the algebraic sums of the scalar components along the ![]() and

and ![]() axes respectively.

axes respectively.

Remark: the apparent locations of vectors on a plane does not affect the vector operations. You can always consider (draw) fixed Cartesian axes, make the vectors concurrent by moving them to the origin of the Cartesian system (tails of the vectors meet at the origin).

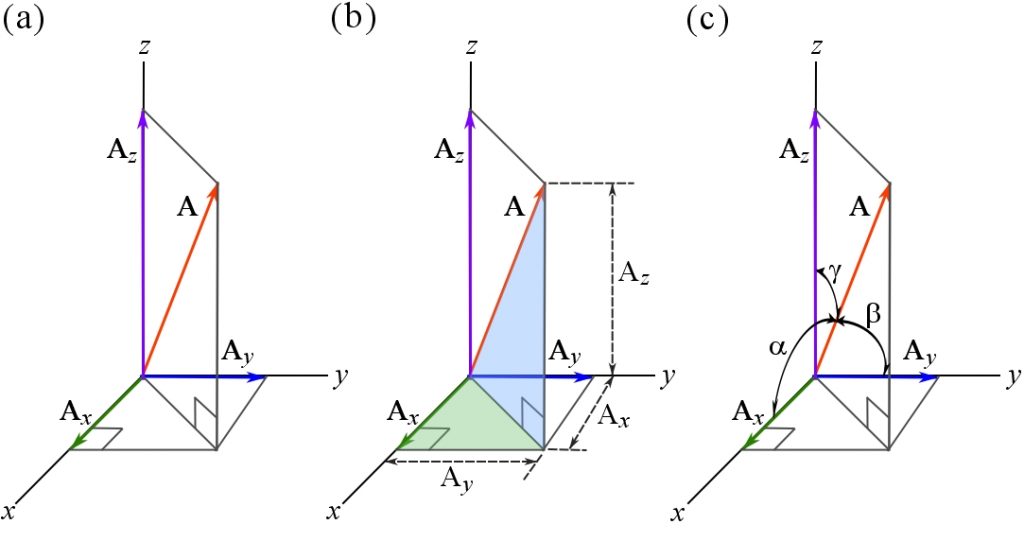

Rectangular vector components of spatial vectors

To treat a vectors in three dimensions, a 3-dimensional (3D) Cartesian (rectangular) coordinate system is to be defined. A common 3D rectangular coordinate system is a right-handed coordinate system. A coordinate systems of three orthogonal axes is said to be right-handed if your right-hand thumb points in the ![]() direction when fingers curl from the (positive)

direction when fingers curl from the (positive) ![]() axis to the (positive)

axis to the (positive) ![]() axis (Figure 18a). In three dimensions, the unit vectors of the axes are denoted by

axis (Figure 18a). In three dimensions, the unit vectors of the axes are denoted by ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() as demonstrated in Figure 18b.

as demonstrated in Figure 18b.

Figure 18. A right-handed Cartesian coordinate system.

The direction of ![]() in the 3D Cartesian coordinate system can be defined by the coordinate direction angles

in the 3D Cartesian coordinate system can be defined by the coordinate direction angles ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() measured from the positive

measured from the positive ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() axes respectively to the vector (Figure 19c). These angles are limited as

axes respectively to the vector (Figure 19c). These angles are limited as ![]() . The following relationship holds between the vector magnitude, the scalar components and the coordinate direction angles:

. The following relationship holds between the vector magnitude, the scalar components and the coordinate direction angles:

![]()

Figure 19. Components of a 3D vector in the 3D Cartesian coordinate system.

![]()

This means knowing two of the angles, the third one is readily obtainable.

Spatial vector operations using CVN (three dimensions)

Once the vectors to be summed are resolved into their components, the same steps as in the planar case should be followed but with including components in the ![]() direction. This means:

direction. This means:

(4) ![]()

in which ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() represent the algebraic sums of the scalar components along the

represent the algebraic sums of the scalar components along the ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() axes respectively.

axes respectively.

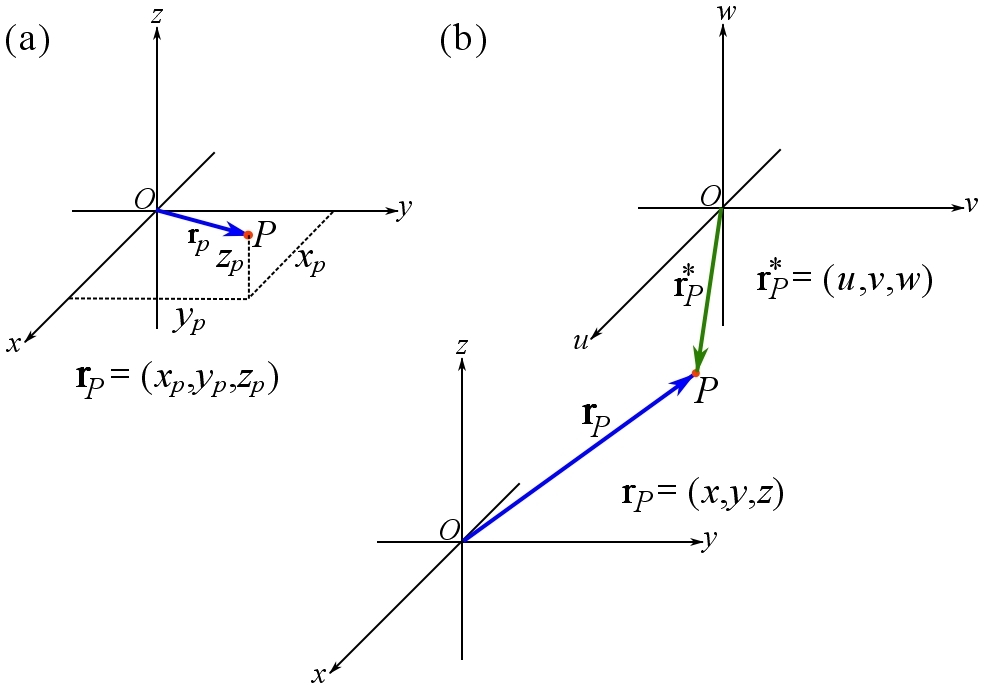

Position vector

Naturally, we can have a perception of a geometric point in space. A point in the space (3D or 2D) can be imagined as an infinitely small dot. The space containing all the geometric points is called the geometric space. In a geometric space, geometric objects (or shapes) are born out of points. For examples, lines, circles, polylines, polygons, surfaces, cubes, etc. We simply refer to the geometric space as the space. The location of a point is the space can be quantitatively determined relative to other points. Thereby, all points can be located relative to one marked point. This point is called the origin of the space and denoted by ![]() . Generally, we form a Cartesian coordinate system in the space and define the origin of the space to be at the intersection of the three (or two) axes of the coordinate system. Therefore, any point in the space is identified by a coordinate triple

. Generally, we form a Cartesian coordinate system in the space and define the origin of the space to be at the intersection of the three (or two) axes of the coordinate system. Therefore, any point in the space is identified by a coordinate triple ![]() in the 3D space, or

in the 3D space, or ![]() in the 2D space. Obviously, the coordinate of the origin is

in the 2D space. Obviously, the coordinate of the origin is ![]() . This approach was introduced by the French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes.

. This approach was introduced by the French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes.

Another approach to locate (identify) a point in the space is by using a vector. Once a point in the space is marked as the origin, a vector (arrow) can be readily drawn (imagined) from the origin of the space, ![]() , to any point,

, to any point, ![]() , in the space. This vector is called the position vector. The position vector is generally denoted by

, in the space. This vector is called the position vector. The position vector is generally denoted by ![]() . To indicate a particular point located by a position vector, the notation

. To indicate a particular point located by a position vector, the notation ![]() or

or ![]() is used. The former notation explicitly express the sense of the direction from the origin

is used. The former notation explicitly express the sense of the direction from the origin ![]() to the point

to the point ![]() , while the latter notation implicitly conveys the sense of the direction. A position vector simply points at a point in the space; is tail is at the origin of the space and its head is at any point to be located (Figure 20a). Constructing a Cartesian coordinate system a the origin as well, the position vector is resolved by the CVN as:

, while the latter notation implicitly conveys the sense of the direction. A position vector simply points at a point in the space; is tail is at the origin of the space and its head is at any point to be located (Figure 20a). Constructing a Cartesian coordinate system a the origin as well, the position vector is resolved by the CVN as:

![]()

where ![]() are the coordinates of the point located by the position vector. Figure 20a shows a position vector in a Cartesian coordinate system locating the points of a space. Choosing a point as the origin of the space is arbitrary; however, a wise choice depending on the problem can simplify the equations. Figure 20b shows a point in a space located by two different coordinate systems and position vectors. Note that the point is the same point but looked at from two different outlooks; therefore it has different coordinates and position vectors in different coordinate systems.

are the coordinates of the point located by the position vector. Figure 20a shows a position vector in a Cartesian coordinate system locating the points of a space. Choosing a point as the origin of the space is arbitrary; however, a wise choice depending on the problem can simplify the equations. Figure 20b shows a point in a space located by two different coordinate systems and position vectors. Note that the point is the same point but looked at from two different outlooks; therefore it has different coordinates and position vectors in different coordinate systems.

Figure 20. Position vector and coordinate systems.

Remark: unit of a position vector or its length has to be specified and written in the calculations. For example you can write ![]() where

where ![]() are the scalar components with the dimension and unit of length, or for example

are the scalar components with the dimension and unit of length, or for example ![]() .

.

Remark: the unit vector ![]() has no dimension. The unit vectors (

has no dimension. The unit vectors (![]() ) of the coordinate system have no dimension as well.

) of the coordinate system have no dimension as well.

Using the coordinate direction angles ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (measured from the positive

(measured from the positive ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() axes respectively), the following equations hold for a position vector in the Cartesian coordinate system:

axes respectively), the following equations hold for a position vector in the Cartesian coordinate system:

(5) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split} \bold r &= x\bold i + y\bold j + z\bold k\quad\quad r=\vert\bold r\vert=\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}\\ x&=r\cos \alpha\quad y=r\cos \beta\quad z=r\cos \gamma\quad \text{for } 0^\circ \le \alpha, \beta,\gamma \le 180^\circ\\ \bold r&=r \hat{\bold r}\ \text{such that }\hat{\bold r}=(\cos\alpha)\bold i +(\cos\beta)\bold j+(\cos\gamma)\bold k \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-378b3b714eab06b8c5693ae00f8cd554_l3.png)

Any vector in the geometric space is a type of a position vector because it connects two points whether or not either marked as the origin. If a (geometric) vector connects two points, say ![]() and

and ![]() , in the space such than non of the points are designated as the origin, the vector is denoted by

, in the space such than non of the points are designated as the origin, the vector is denoted by ![]() and called a displacement vector. The displacement vector in fact expresses the displacement of the position vector from point

and called a displacement vector. The displacement vector in fact expresses the displacement of the position vector from point ![]() to point

to point ![]() . To understand this concept, imagine two points

. To understand this concept, imagine two points ![]() and

and ![]() respectively located by the position vectors

respectively located by the position vectors ![]() and

and ![]() in the space already having a defined origin

in the space already having a defined origin ![]() and a Cartesian coordinate system (Figure 21). The vector (arrow) from the point

and a Cartesian coordinate system (Figure 21). The vector (arrow) from the point ![]() to the point

to the point ![]() is the displacement vector

is the displacement vector ![]() . By the rules of vector addition, we can write:

. By the rules of vector addition, we can write:

(6) ![]()

By using the CVN:

(7) ![]()

Interpreting the above equations geometrically, we understand that if an object is displaced along the vector ![]() , its position is changed from the point

, its position is changed from the point ![]() , located by

, located by ![]() , to the point

, to the point ![]() located by

located by ![]() . The quantity

. The quantity ![]() is the length of displacement.

is the length of displacement.

Figure 21. Position and displacement vectors.

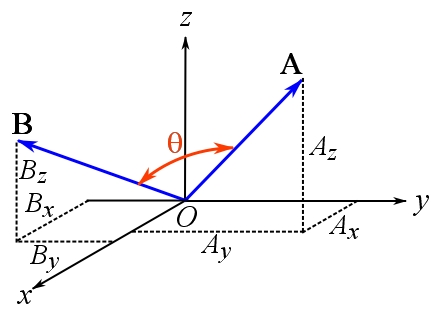

Dot product

The dot product, also called the scalar product, is an operation that takes two vectors and returns a scalar. The dot product of vectors ![]() and

and ![]() , denoted as

, denoted as ![]() and read “

and read “![]() dot

dot ![]() ” is defined as:

” is defined as:

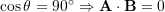

(8) ![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the angle between the two vectors (Figure 22)

is the angle between the two vectors (Figure 22)

Figure 22. Configuration of two vectors for the dot product.

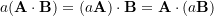

- Commutativity:

- Associativity (scalar multiplication):

- Distributivity:

The proofs of the first two properties are by direct using the dot product definition (Eq. 8). The proof for the third property is by expanding the right hand side of the equation using the CVN notation and factoring the scalar components of ![]() . Dot product using the CVN is explained below.

. Dot product using the CVN is explained below.

Other properties of the dot product

- Dot product of a vector by itself gives its squared magnitude:

.

. - Dot product of two perpendicular vectors is zero:

.

. - If

then

then  .

. - If

then

then  .

. - Dot product by the zero vector is zero:

.

.

These properties are easily proved by using Eq. 8.

Formulation of the dot product using CVN

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be two vectors with their scalar components

be two vectors with their scalar components ![]() and

and ![]() . Using the CVN, we can write:

. Using the CVN, we can write:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split} \bold A\cdot \bold B&=(A_x\bold i +A_y\bold j+A_z\bold k )\cdot(B_x\bold i +B_y\bold j+B_z\bold k)\\ &\text{by the distributivity property}\\ &=A_xB_x(\bold i\cdot \bold i)+A_xBy(\bold i\cdot \bold j)+A_xB_z(\bold i\cdot \bold k)\\ &+A_yB_x(\bold j\cdot \bold i)+A_yBy(\bold j\cdot \bold j)+A_yB_z(\bold j\cdot \bold k)\\ &+A_zB_x(\bold k\cdot \bold i)+A_zBy(\bold k\cdot \bold j)+A_zB_z(\bold k\cdot \bold k) \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ee7c7f6bd9a6e109a536ea2c405432bc_l3.png)

The dot product of the unit vectors, by the dot product properties, are:

![]()

Therefore,

(9) ![]()

This result expresses that the dot product of two vectors written in their CVN is obtained by multiplying their corresponding scalar components and summing over these product algebraically. Equation 9 indicates that calculating the dot product (Eq. 8) does not need the magnitudes of two vectors and the angle between them, if the vectors are resolved in the Cartesian system.

Application of the dot product: finding the angle between two vectors

Dot product can be used to find the angle formed between two vectors or two intersecting line. This property facilitate the calculations particularly when solving problems in three dimensions. The angle between two vectors is obtained by solving Eq. 8. for the angle term:

(10) ![]()

in which ![]() is found from Eq. 9.

is found from Eq. 9.

The above equation can be manipulated as:

![]()

in which ![]() and

and ![]() are the unit vectors of

are the unit vectors of ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. This result naturally states that the angle between two vectors only depends on their directions and not on their magnitudes.

respectively. This result naturally states that the angle between two vectors only depends on their directions and not on their magnitudes.

Application of the dot product: orthogonal projection of a vector

In many problems, we need to resolve a vector on a particular line or lines in the space. To be more precise, the component of a vector along a particular direction or axis is to be found. Decomposing a vector onto the Cartesian axes is already demonstrated. In this section, we explain decomposing a vector on general lines or axes in space using the dot product. Using the dot product makes the calculation easier specially in three dimensions.

Consider a non zero vector ![]() in the three dimensional space and a line

in the three dimensional space and a line ![]() intersecting the tail of the vector at a point

intersecting the tail of the vector at a point ![]() (Figure 23a). This line accompanies the direction along which we want to decompose the vector. The positive direction of the line is determined by a unit vector say

(Figure 23a). This line accompanies the direction along which we want to decompose the vector. The positive direction of the line is determined by a unit vector say ![]() . As previously mentioned, a line along with a colinear vector (determining the positive direction) is called an axis. It is intended to resolve

. As previously mentioned, a line along with a colinear vector (determining the positive direction) is called an axis. It is intended to resolve ![]() into two components as (Figure 23b):

into two components as (Figure 23b):

(11) ![]()

where ![]() is the component of

is the component of ![]() parallel to (colinear with) the line and, indeed, the unit vector

parallel to (colinear with) the line and, indeed, the unit vector ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the component of

is the component of ![]() perpendicular to the line and, of course, the unit vector

perpendicular to the line and, of course, the unit vector ![]() . The symbol

. The symbol ![]() denotes perpendicularity.

denotes perpendicularity.

Figure 23. Orthogonal projection.

(12) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split} A_a=A\cos \theta&=\bold A\cdot\bold u_a \\ \bold A_a&=A_a\bold u_a\\ \vert\bold A_a \vert&=\mid A_a\mid \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a61b6c08d2dee74d716deae7c28a2c1e_l3.png)

It should be noted that ![]() is the scalar component of

is the scalar component of ![]() resolved along the direction of

resolved along the direction of ![]() . Using the dot product

. Using the dot product ![]() to calculate

to calculate ![]() may result in a negative scalar if the angle between

may result in a negative scalar if the angle between ![]() and

and ![]() are larger than

are larger than ![]() . In such a case, the direction of

. In such a case, the direction of ![]() is in the opposite direction of

is in the opposite direction of ![]() .

.

The perpendicular component of ![]() can be then obtain by writing:

can be then obtain by writing:

![]()

The magnitude of the perpendicular component can be calculated either by ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

In practice, ![]() and

and ![]() can be readily used if

can be readily used if ![]() in known, otherwise

in known, otherwise ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() can be utilized if the components of the vectors in CVN are known.

can be utilized if the components of the vectors in CVN are known.

As a special case, orthogonal projection is used to find the scalar components of a vector in a Cartesian frame. This is done by writing:

(13) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split} A_x&=\bold A\cdot \bold i\\ A_y&=\bold A\cdot \bold j\\ A_z&=\bold A\cdot \bold k \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-42598afd087d6115d59a276db97e7317_l3.png)

Cross product

The cross product of two vectors is an operation that takes two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() and returns a vector

and returns a vector ![]() . This operation is denoted by

. This operation is denoted by ![]() and is read “C equals A cross B”. The resultant vector

and is read “C equals A cross B”. The resultant vector ![]() has a magnitude,

has a magnitude, ![]() ,and a direction denoted by

,and a direction denoted by ![]() .

.

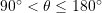

For ![]() The magnitude of

The magnitude of ![]() is defined as:

is defined as:

(14) ![]()

in which ![]() is the angle between the two vectors.

is the angle between the two vectors.

The definition of the magnitude of the cross product implies that, ![]() if two non-zero vectors are colinear.

if two non-zero vectors are colinear.

By definition, ![]() is perpendicular to both

is perpendicular to both ![]() and

and ![]() which are not colinear and it is direction is specified by the right-hand rule. In other words,

which are not colinear and it is direction is specified by the right-hand rule. In other words, ![]() is perpendicular to the plane containing the non-colinear vectors

is perpendicular to the plane containing the non-colinear vectors ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that ![]() is in the direction of the thumb following the right-hand rule (Figure 24).

is in the direction of the thumb following the right-hand rule (Figure 24).

Figure 24. Cross product.

Properties of Cross product

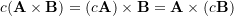

- Anti-commutativity:

- Associativity: for a scalar

,

,

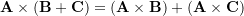

- Distributivity:

Cross product in CVN

In a Cartesian frame the following relationships are readily obtained for the mutually perpendicular unit vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{matrix} \bold i\times \bold i=\bold 0 &\bold i\times \bold j=\bold k & \bold i\times \bold k=-\bold j \\ \bold j\times \bold i=-\bold k & \bold j\times \bold j=\bold 0 & \bold j\times \bold k=\bold i \\ \bold k\times \bold i=\bold j & \bold k\times \bold j=-\bold i & \bold k\times \bold k=\bold 0 \\ \end{matrix} \]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5957262068ec49c412761182cc347572_l3.png)

Based on the above results and the properties of the cross product, the cross product of two vectors in their CVN is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{split} \bold A&=A_x\bold i + A_y\bold j+A_z\bold k\quad , \quad \bold B=B_x\bold i+B_y\bold j+B_z\bold k\\ \bold A\times \bold B&=(A_xB_x)\bold i\times \bold i +(A_xB_y)\bold i\times \bold j +(A_xB_z)\bold i\times \bold k\\ &+(A_yB_x)\bold j\times \bold i +(A_yB_y)\bold j\times \bold j +(A_yB_z)\bold j\times \bold k \\ &+(A_zB_x)\bold k\times \bold i +(A_zB_y)\bold k\times \bold j +(A_zB_z)\bold k\times \bold k \end{split}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b289cdf6a59bd07c0bf55e299f6aac27_l3.png)

leading to:

![]()

This result need not to me memorize and can be obtained by calculating the following determinant symbolically:

(15) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \bold A\times\bold B = \begin{vmatrix} \bold i & \bold j & \bold k \\ A_x & A_y & A_z \\ B_x & B_y & B_z \\ \end{vmatrix}\]](https://engcourses-uofa.ca/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-77d6966ef6d0f5d0200f157a3177907a_l3.png)